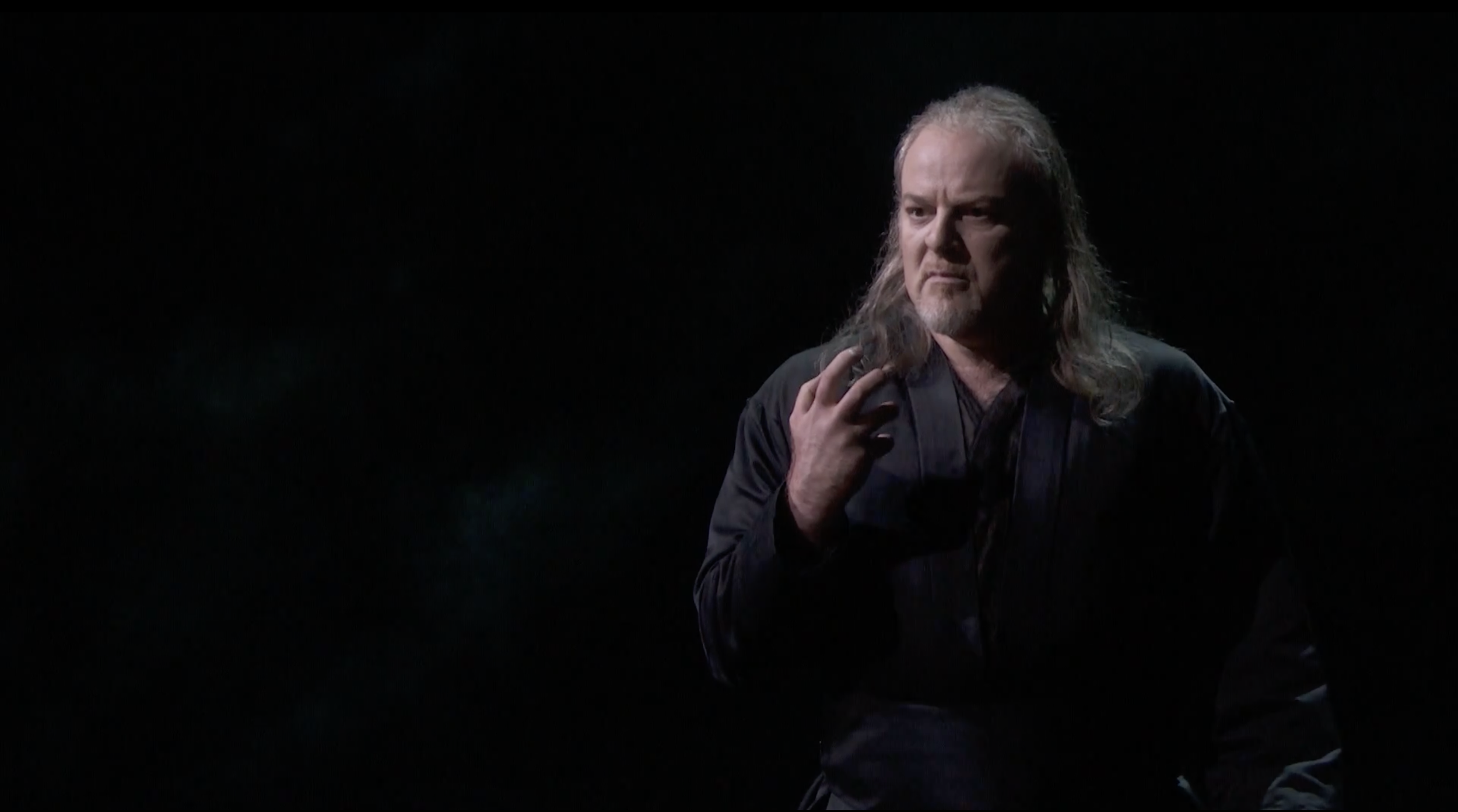

Januar: Der Fliegende Holländer

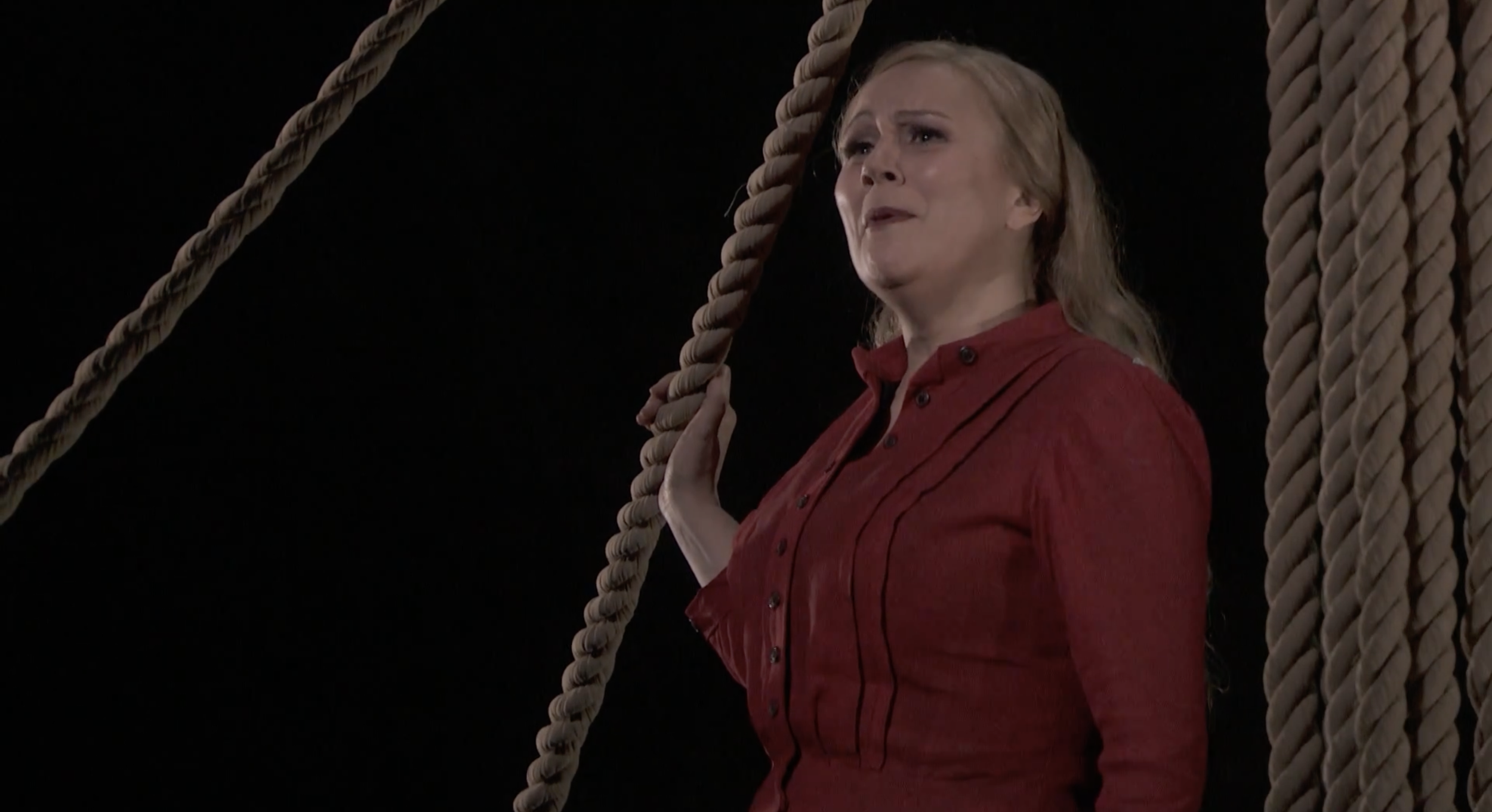

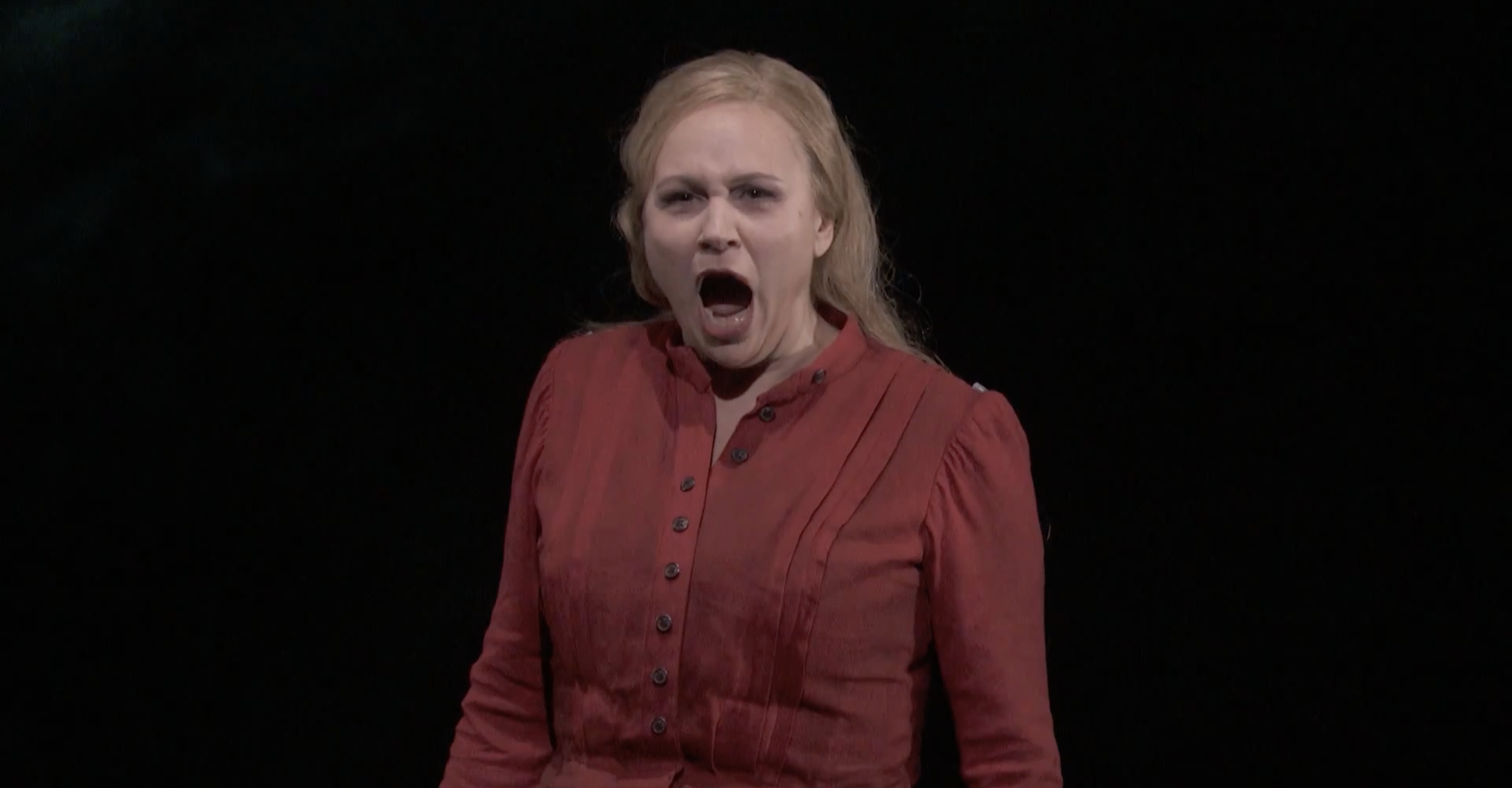

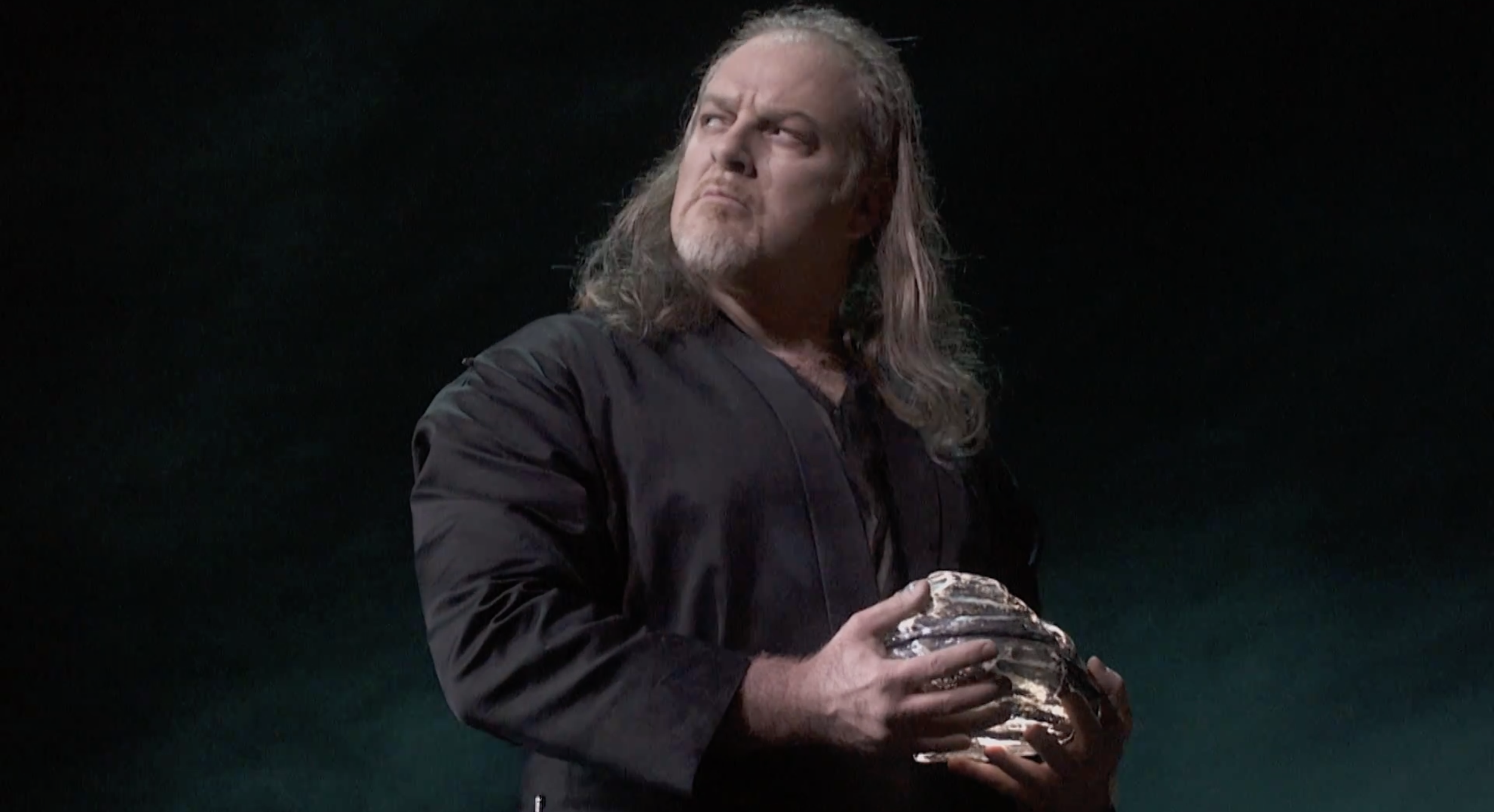

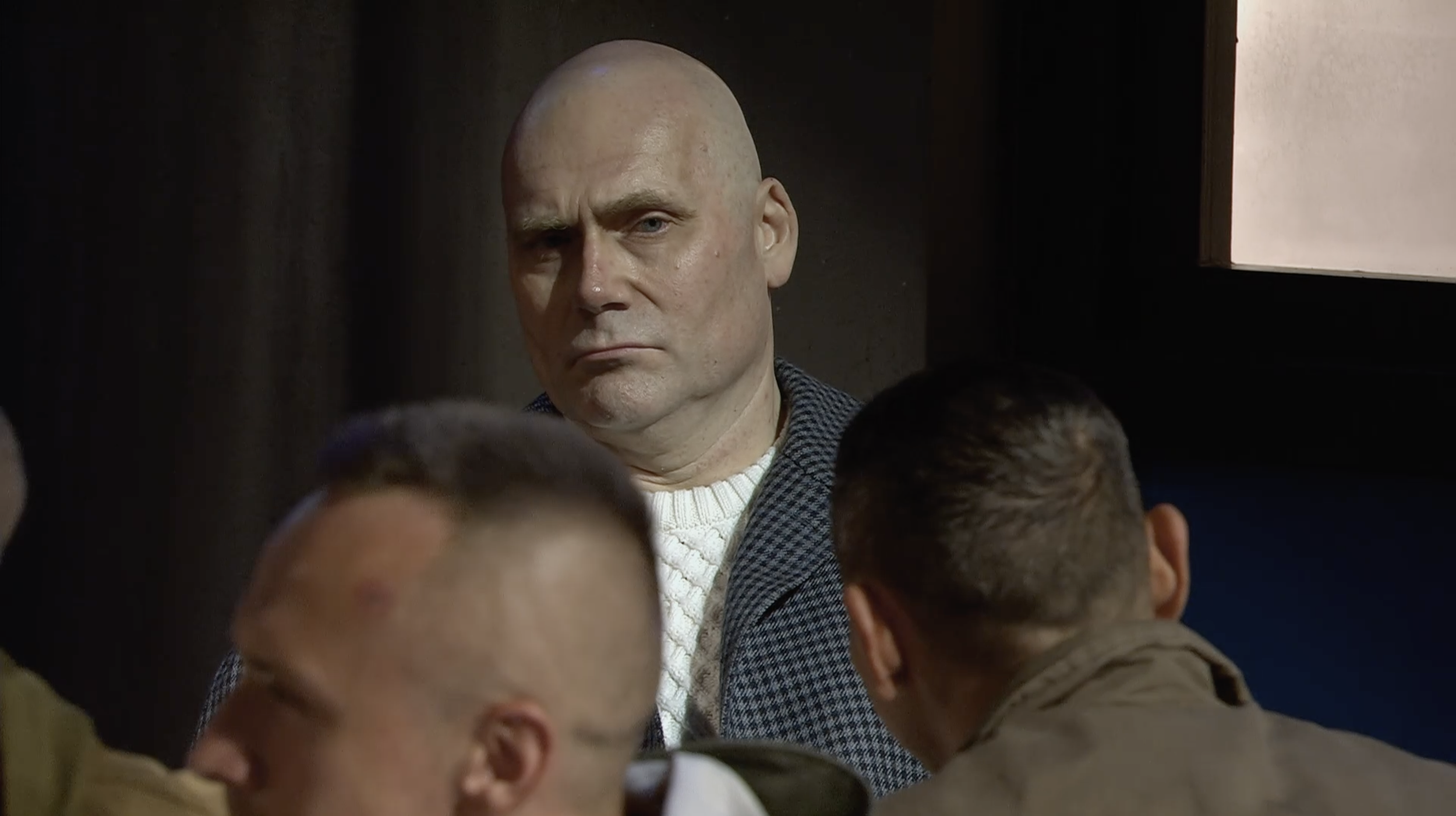

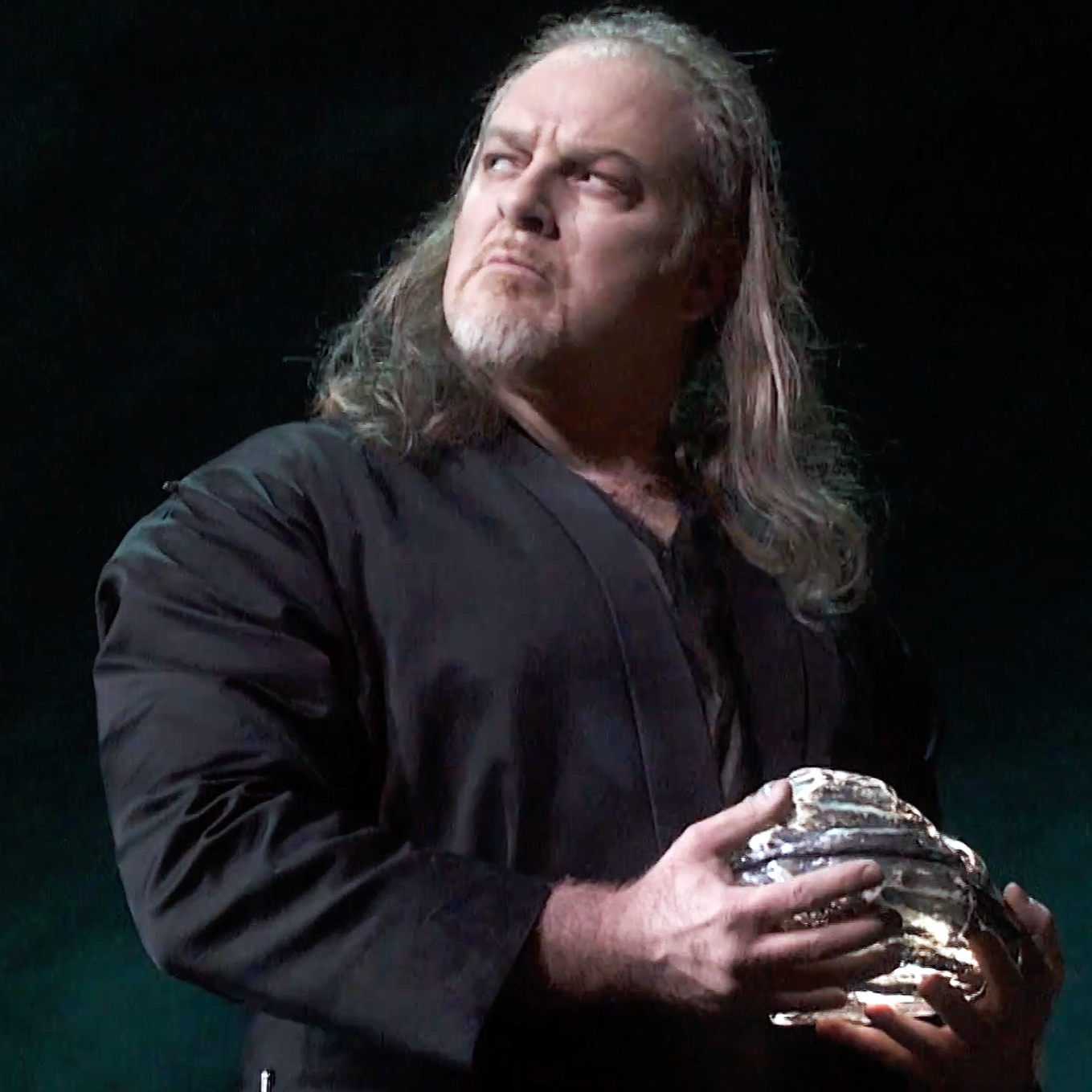

Craig Colclough performing the role of the Dutchman in the opera Der Fliegende Holländer, Göteborgs Opera

Themen: Sehnsucht, Wanderschaft, Stürme, Warten, Geistererscheinungen

Element: Wasser und Winterdämmerung

This walk treats Wagner not as repertoire, but as a composed method for moving through the city

Das Ergebnis auf einen Blick

Dauer: 3–4 Hours: A full-day wander if you pause for listening, reflection, and silent coda yet flexible enough to break into segments.

Distanz: 2.5–3 miles: Battery Park → Staten Island Ferry crossing → Old Slip → Micro-loops through Financial District.

Beste Zeit: Mid-afternoon into dusk. When the harbor light shifts, and the wind off the water feels most dramatic.

Wetter:

Wind enhances meaning: Like the storm and sea imagery of the Holländer overture.

Rain acceptable / preferred: Rain and wind can sharpen the sense of elemental exposure that the opera conjures.

Zugänglichkeit:

Mostly flat terrain: Battery Park paths, ferry boarding, short street walks.

One ferry ride (free) included: A key node in the sequence.

Essentieller Moment:

The Staten Island Ferry crossing with Die Frist ist um, Dutchman’s monologue. The ritual separation from Manhattan, placing you between worlds and grounding the Holländer’s loop of return and exile.

Language Anchor (German Phrase of the Month):

Die Frist ist um / The time is up: A capsule of the Dutchman’s curse and a frame for standing on the ferry watching Manhattan recede.

Wort des Weges

Sehnsucht (pronounced: ZAYN-zookt): Not longing for what was, but for what has never yet been reached. In Wagner, Sehnsucht is not sentimental. It is restless, forward-pulling, unresolved. It is the condition of the Dutchman himself.Condemned not to drift endlessly, but to desire endlessly. New York, in January, understands this word instinctively.

Wanderschaft: Distinct from Wandern (hiking) or Reise (travel). It carries a specific historical and cultural weight: the journeyman's tradition (Gesellenwanderung), the Romantic walker, and the sense of purposeful unrootedness that the walk itself enacts.

Sturm: From Sturm und Drang to the harbor overture, this is a word with enormous cultural freight in German. Moving through its meteorological meaning into its use in art, literature, and music.

Warten: The German verb for waiting, but in the context of the Dutchman's curse, exploring how German handles temporal states differently: warten auf (waiting for), erwarten (to expect), and the philosophical weight of unresolved waiting.

Geistererscheinung: Ghost appearance / apparition. A compound noun that does a lot of work. Use it as a gateway into how German builds compound words, and what Geist means in German culture more broadly (spirit, mind, ghost — all in one).

Thematischer Rahmen: Der Fliegende Holländer

January is an exploration of ending and repetition, of being caught between departure and return. A condition Wagner made literal in Der Fliegende Holländer, the opera about a cursed mariner fated to circle without rest until redemption breaks the loop.

In Wagner’s mythology, the Dutchman’s curse is existential: bound to the seas, allowed ashore only every seven years, never finally at rest. This is less a narrative than a condition of being. A liminal state between winds that drive and waters that hold. In Der fliegende Holländer, the opera’s metaphysics are about inevitability and yearning, about the impossible contract between desire and deliverance.

Lower Manhattan, Battery Park, the ferry routes, the slips once cut into the waterfront, is the perfect urban analog for this metaphysical frame. At places like Castle Clinton, points of immigration and entertainment, the city itself looks like a ghost ship: human purposes repurposed over time, tides of arrivals rewritten as monuments of departure. The harbor wind becomes the chorus; the ferries, ceaseless arcs that never truly land, become the Dutchman’s own circuit. The urban waterfront makes the opera’s condition palpable, not abstract.

Wagner’s German words, Die Frist ist um (the time is up) become conceptual keystones for standing on the ferry deck as Manhattan shrinks behind you. They are not foreign phrases to be glossed, but anchors for experience: a way of letting language move through you while your body moves through the harbor.

This month, then, is an invitation to notice the unfinished, the in-between, and the non-resolution. Not as metaphors of art, but as lived contours in the city’s edges and your own steps.

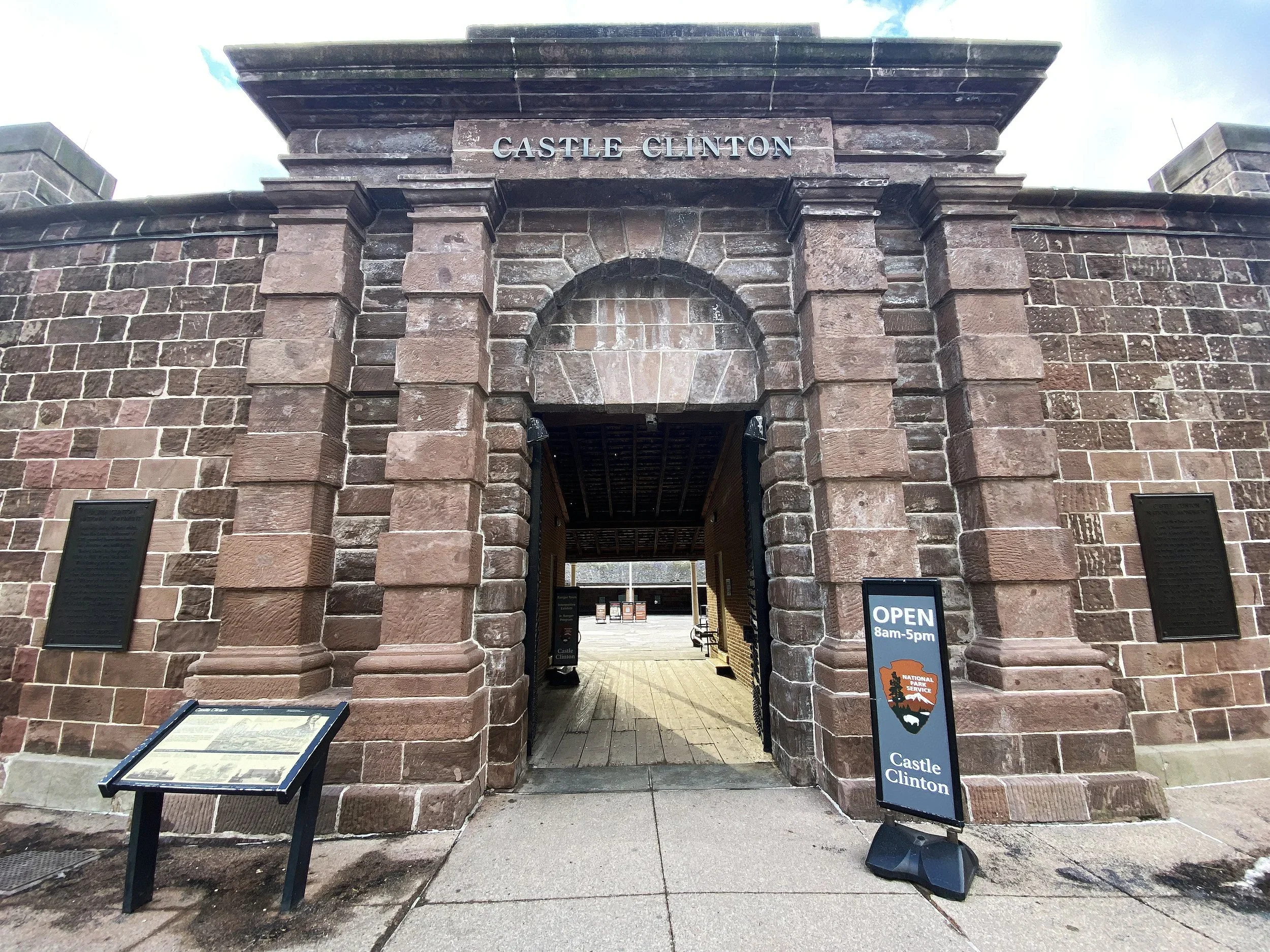

Hafensturm: Battery Park & Castle Clinton

Getting There

Take the 4/5 to Bowling Green, or the 1 to South Ferry, or R/W to Whitehall St–South Ferry.

From Bowling Green: Walk south along State Street; Battery Park opens in front of you.

Aim for Castle Clinton, the circular reddish stone fort just inside the park.

Walk: Harbor Edge with the Overture

Track: Flying Dutchman Overture

Route

Enter the park near State St & Battery Pl.

Walk clockwise along the water’s edge, keeping the harbor on your left.

Pace the walk so the opening string tremolo happens as you first see the Statue of Liberty and the ferry wakes in the water.

When the big brass theme hits, look back at the skyline from near the East Coast Memorial. You get towers, masts, and open water in one shot.

East Coast Memorial, Battery Park City

What to Look at / Think About

Wagner claimed Dutchman came from a brutal sea crossing from Riga to London in 1839

Storms, almost wrecked, ship forced into a Norwegian harbor.

The harbor traffic is the 21st-century equivalent:

Cruise ships, ferries, tourist boats, all tracing fixed routes that must feel eternal to their crews.

Think of the overture as the psychology of a storm:

Low-string tremors as wind shift

Sharp brass as waves hitting the hull

Calmer middle as the deceptive lull before the curse reasserts itself.

View looking North of Battery Park

Walk: Castle Clinton: Ghost Ship / Immigrant Ship

Track: Stay with the overture, or pause and restart from the quieter middle.

From the harbor edge, cut inland toward Castle Clinton.

What Castle Clinton is Doing Here

Built 1808–1811 as a defensive fort called the West Battery, it became Castle Garden, a 6,000-seat entertainment venue, one of the city’s first big European-style opera houses.

From 1855–1890 it shifted roles and became the main immigrant receiving depot, processing more than 7–8 million people before Ellis Island took over.

So you’re standing in a place that was:

A coastal fort

A proto-opera house

A bureaucratic machine for newly arrived humans

It’s almost comically perfect for Dutchman. A building which keeps being repurposed, housing different waves of people blown in by history.

Entrance threshold to Castle Clinton

Micro-Circuit Around the Fort

Stand at the front gate with Castle Clinton carved above you. Start the soft middle section of the overture.

Walk slowly around the exterior, hugging the circular wall.

When the music surges again, imagine 19th-century immigrant ships lining up just off this seawall. Every ship is someone’s Flying Dutchman: forced crossings, bad weather, unknown futures.

If you go inside:

Pick a corner by the wall.

Let the final section of the overture run while you look up at the stone and imagine it lit as an opera house, then filled with benches and registration desks.

Surrounding original fortified walls of Castle Clinton

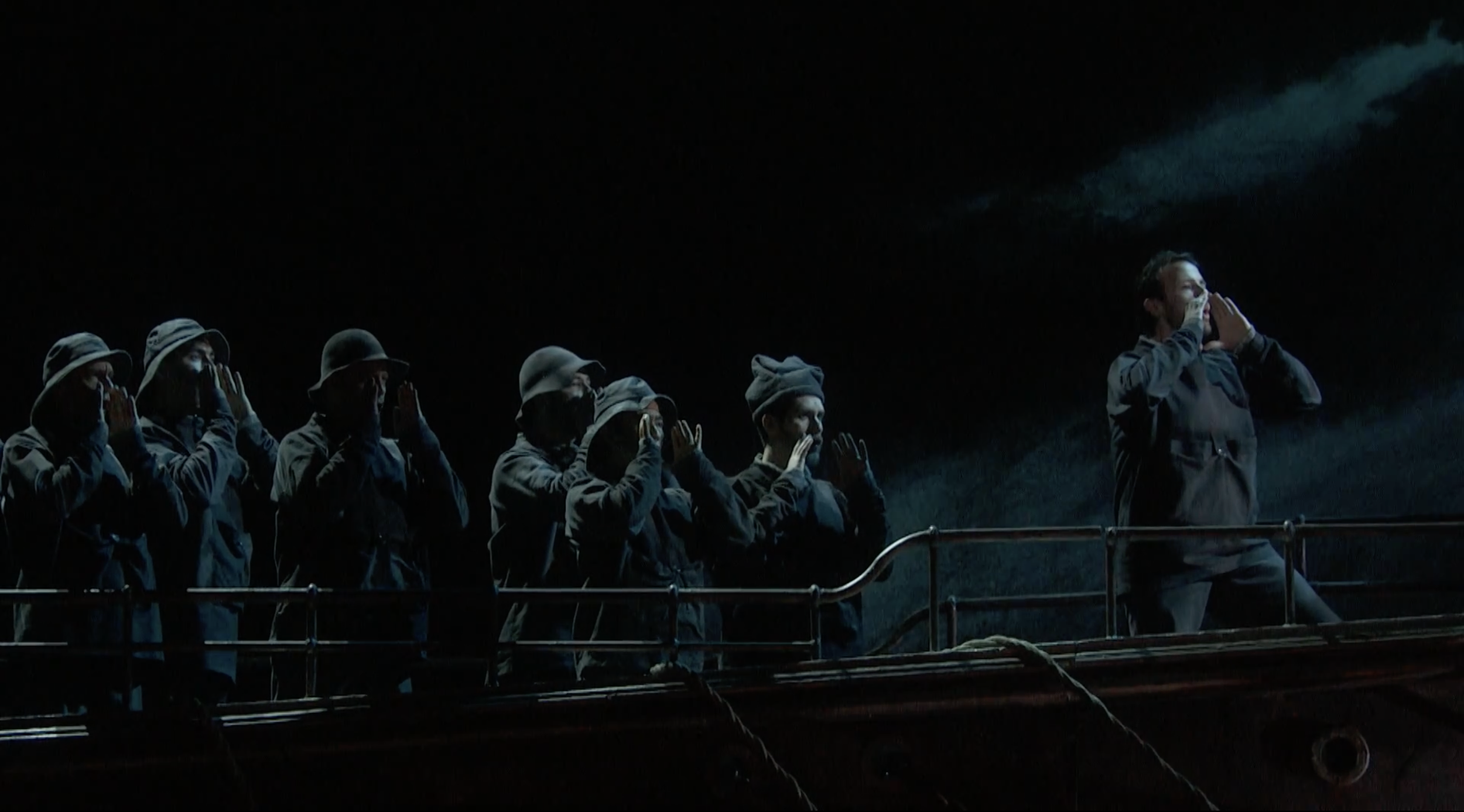

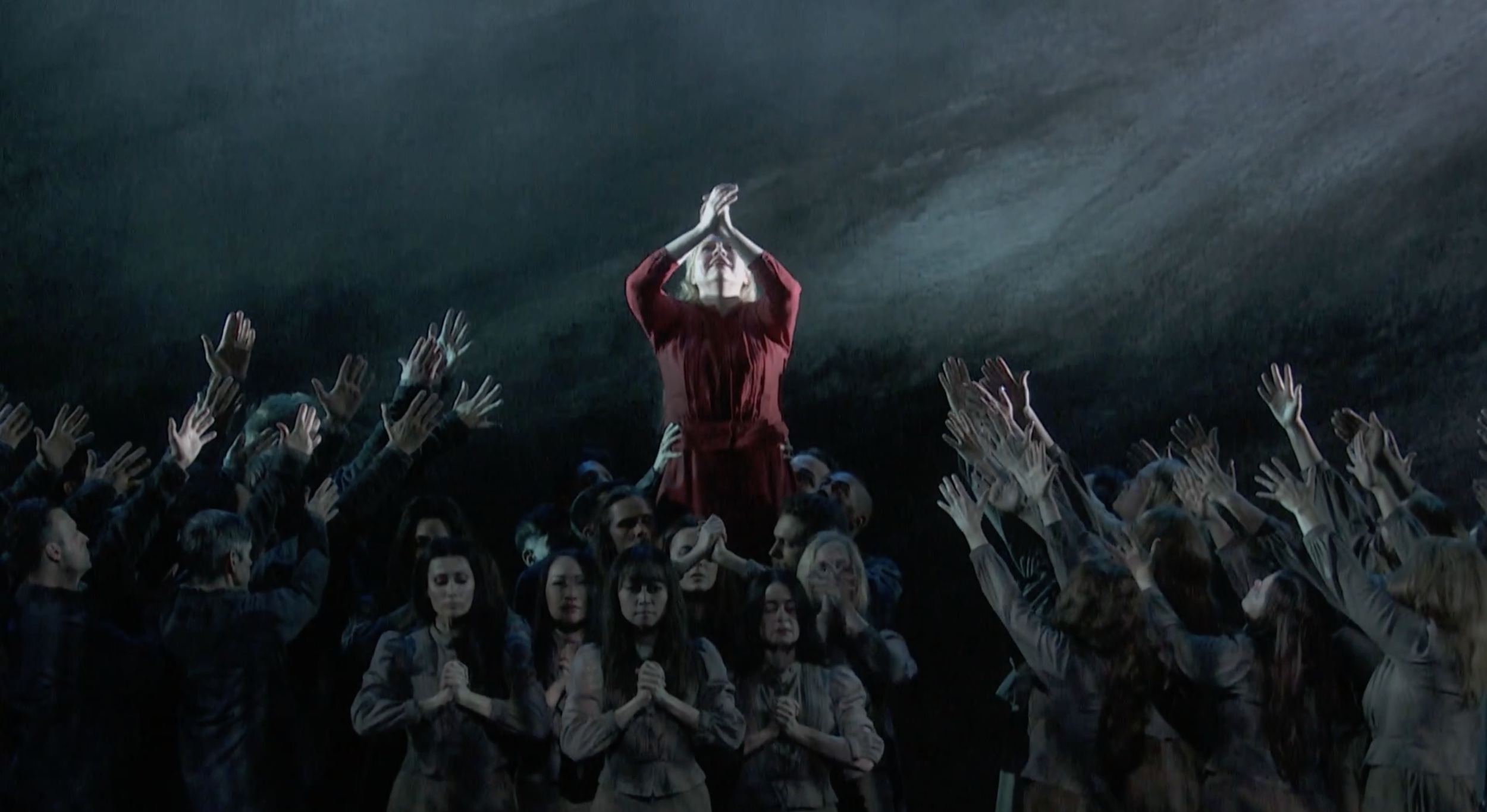

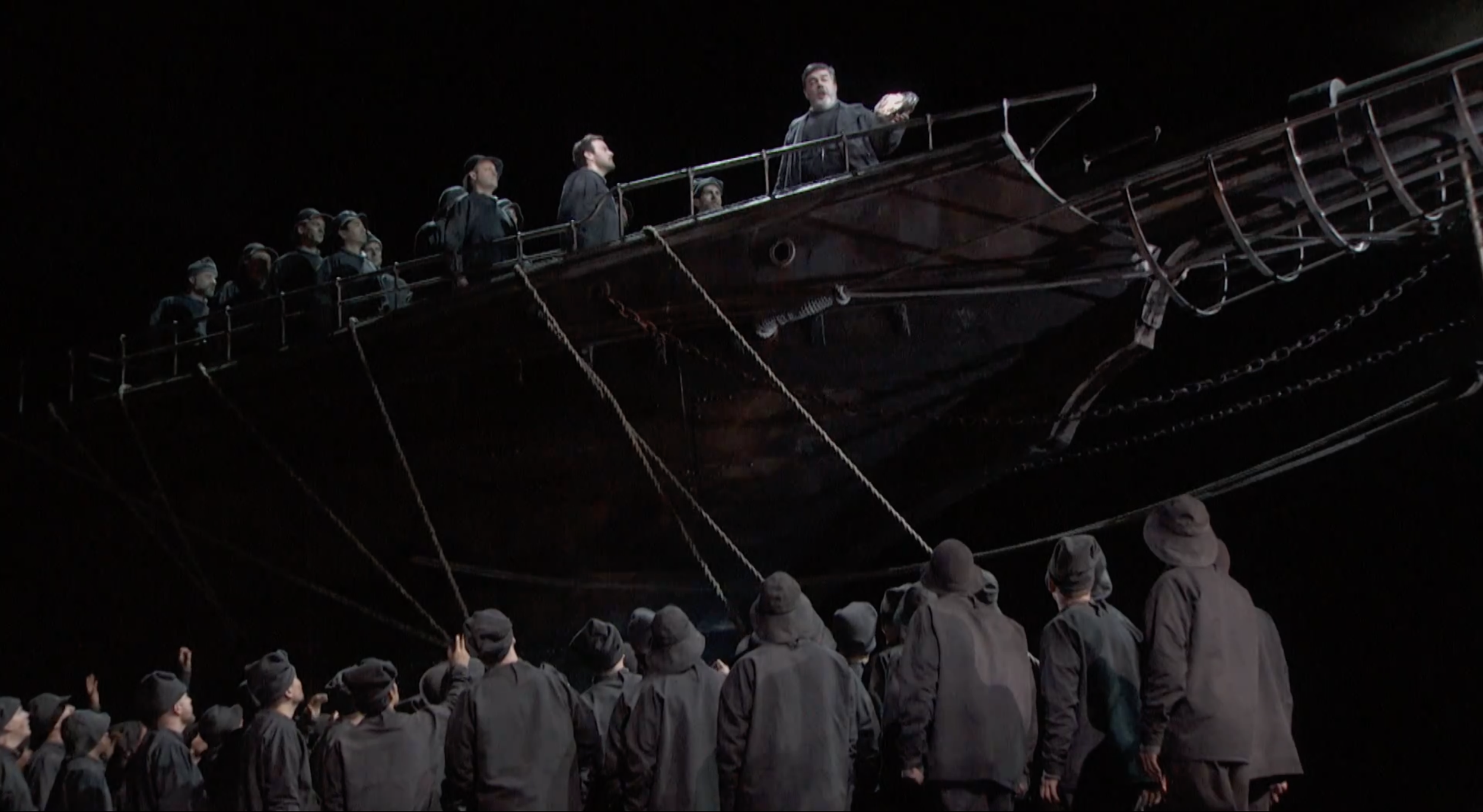

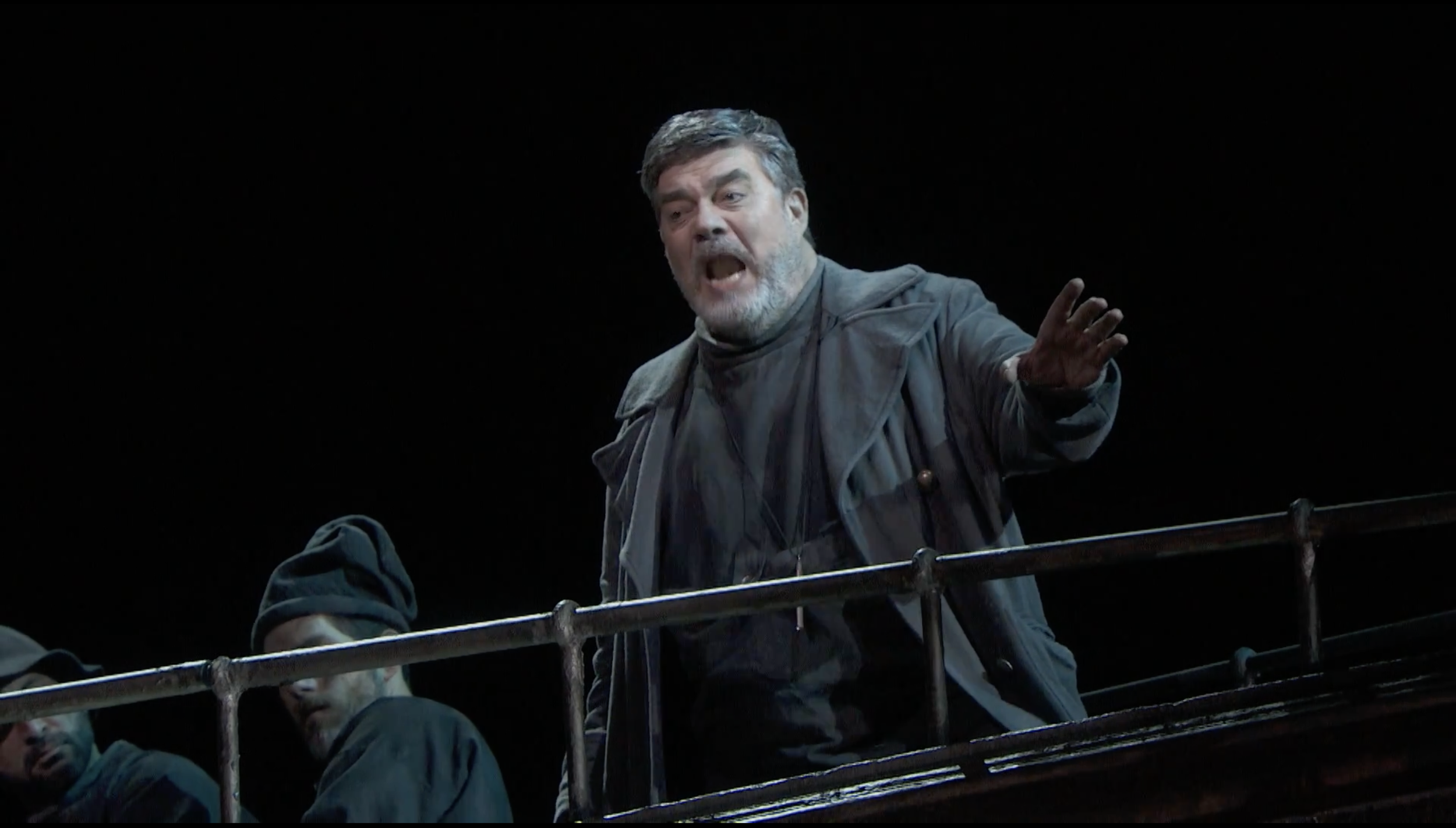

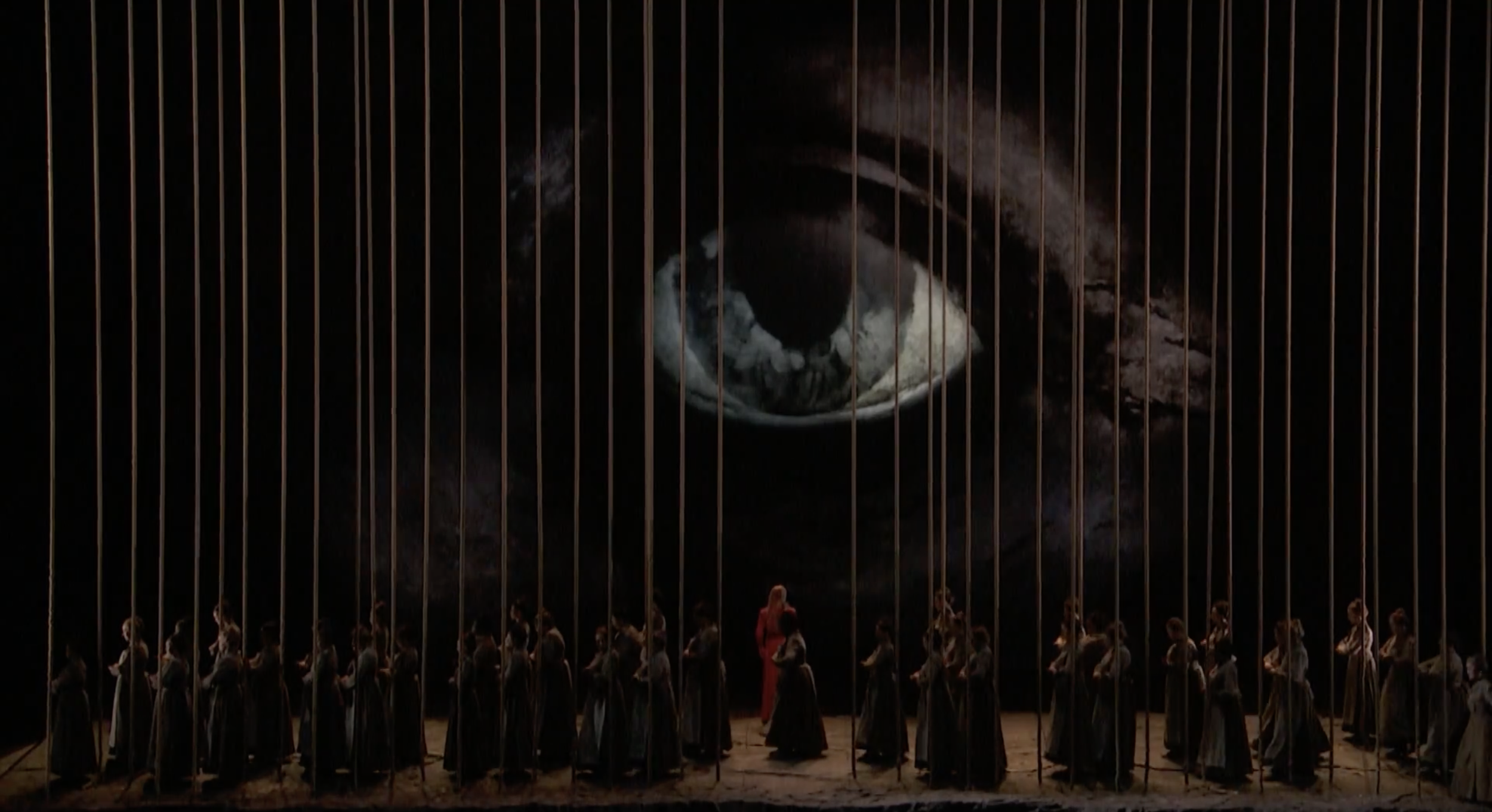

Der Fliegende Holländer, Metropolitan Opera, March 2020

Die Ewige Überquerung: Staten Island Ferry

Entrance to The Staten Island Ferry, Whitehall Street

Getting onto the Ferry

Walk east across the park to the Whitehall Terminal (signed Staten Island Ferry).

It’s free. Just board the next departing boat.

Outbound Leg: Die Frist ist um

Track: Die Frist ist um

How to Stage it

Once aboard, go to the rear deck so you’re facing back toward Manhattan.

Start the track as the ferry just begins to move off the dock.

Let the Dutchman’s opening lines ride over the moment when Manhattan starts to slide away.

The Staten Island Ferry

What to Watch

The wake the ferry cuts. A literal track in the water, slowly erased.

The towers of the Financial District shrinking, then regrouping as one dense silhouette.

Every few minutes you pass other ferries doing exactly the same thing.

Think: They never stop. Crews cycle, boats cycle, the route is effectively eternal.

Tie this to the Libretto’s Logic

The Dutchman is allowed ashore once every seven years.

If he can’t find redemption he’s hurled back onto the sea.

The ferry crews get a much kinder deal, but you’re still watching a small human system enact an infinite loop.

When the aria ends, let a minute of harbor silence stand in your ears.

No music for a stretch. Just engine noise and wind.

Watching the ferry’s wake as the Manhattan skyline recedes into the distance

Return Leg: Overture Reprise and Harbor as Stage Set

On the way back, flip the perspective:

This time:

Stand at the front deck facing Manhattan.

Use the big return of the main theme as your cue to watch the skyscrapers loom closer, like cliffs.

Think of New York itself as the cursed ship this time:

Massive, noisy, never allowed to rest, burning fuel 24/7 to keep moving.

Watching the ferry’s wake while listening to the overture of The Flying Dutchman

Der Fliegende Holländer, Bayreuth Festival, 2021

The Wesendonck Slip: 12 Old Slip & Guardian Life

Walk: From the Staten Island Ferry to Old Slip

Exit Whitehall Terminal back onto State Street.

Walk north-east along the park edge, then cut onto Water Street.

Continue up until you reach Old Slip: A short diagonal street slicing between Water St and South St.

Original site of 12 Old Slip (now the 77 Water Street Tower)

What You’re Looking For

The corner where 12 Old Slip once stood (now part of the 77 Water Street Tower).

Across the way is the tall brick slab of the Guardian Life Building, at 7 Hanover Square, Guardian’s late-20th-century HQ.

Guardian Life Building, at 7 Hanover Square

Why this Matters for Wagner

Alex Ross’s thread: The Rest Is Noise

In the 1830s, young Otto Wesendonck joins merchant William Loeschigk to launch a textile-import firm at 12 Old Slip, specializing in fine silks.

The firm thrives. Otto returns to Europe as its representative.

In Zurich, Otto and his wife Mathilde build a villa. Wagner moves in, becomes infatuated with Mathilde, composes the Wesendonck Lieder to her texts, and folds parts of that music into Tristan und Isolde.

Otto’s brother Hugo Wesendonck comes to America after the 1848 revolutions, founds Germania Life Insurance in 1860, and becomes a major player in New York finance.

Germania rebrands as Guardian Life in 1917 amid World War I anti-German sentiment, and by a quirk of history, Guardian’s HQ ends up directly across from Old Slip, almost on top of Otto’s original address.

So the money and risk calculus that made Tristan and late Wagner possible starts here, on this short, easy-to-miss street.

The East River from Slip A

Walk: Standing in the Slip with Senta

Track: Senta’s Ballad

Setup:

Stand roughly where Old Slip intersects Water Street, facing toward the East River.

Start Senta’s Ballad and imagine you’re the one telling the legend of a ghost ship

But your ship is a trading company, a flow of bolts of silk, credit, and speculative risk.

Things to Notice:

Old Slip was historically just that, a slip, a cut into the shoreline where ships docked.

Later filled in as the island expanded.

You’re walking on ground which used to be water, where hulls scraped barnacles and crews threw down ropes.

Senta is obsessed with a story she’s been told since childhood.

Old Slip is the physical residue of a story New York tells itself: that trade risk always pays off in the long run.

As the Ballad climaxes, look up at 77 Water Street and the surrounding glass towers.

Those are this century’s ships.

The FDR Overpass alongside the East River

Walk: The Duet Wie aus der Ferne and the Echo Between Continents

Now:

Walk slowly along Old Slip toward South Street, letting the duet’s strange, suspended atmosphere sit on top of honking trucks and office deliveries.

Pause when you reach the South Street end, where you can glimpse the FDR, the piers, and the East River.

Think about what this duet is:

The Dutchman and Senta finally confronting the way they’ve been imagining each other for years.

It’s emotionally ambiguous.

Part salvation, part mutual hallucination.

Now add Wagner’s almost-move to America:

In his last years, he repeatedly fantasized about leaving Europe for the U.S., telling Cosima America was the only place on the map he could look at with any pleasure, likening it to ancient Greece.

He even sketched a plan where American patrons would raise $1M (19th-century money) to relocate him.

In return the U.S. would get exclusive rights to Parsifal and future works.

You’re standing on a street which quietly proves the fantasy wasn’t as far-fetched as it sounds.

Wagner’s network was already economically attached to New York through the Wesendoncks.

Mikro-Rundreise durch die Canyons: Kapital als Fluch

Route

From the South Street end of Old Slip:

Turn left (north) briefly on South Street, then cut up Front Street or Water Street.

Work your way west toward Broad Street, then north to Wall Street.

You’re essentially doing a small triangle:

Old Slip, Water/Front, Broad, Wall Street and back toward Bowling Green.

Track: Just the first 4–5 minutes of the Overture again.

Looking up into the canyons of Wall Street

What to Notice

The Financial District streets are narrow, shadowy canyons.

The buildings are cliffs. Signs of insurance companies, banks, and law firms are everywhere.

This is what happened after all those ships in Castle Garden, after all those bolts of silk on Old Slip.

The city financialized the sea.

Wagner’s Dutchman trades his soul for a ship that can’t sink.

Wall Street trades complex futures for the illusion that nothing will crash.

As the music builds, think of the Dutchman’s curse less as metaphysics and more as a business model:

Keep sailing, keep making deals, never dock for too long.

Every seven years, someone promises to fix it.

It never quite works.

Optionaler Abend: Stille Ausklänge im Wagner Park

If You Have One Last Move in You:

Drift back into Battery Park and walk around to Robert F. Wagner Park without headphones.

Stand again near Castle Clinton or by the water.

No music this time. Just harbor noise, ferry horns, the hum of the city.

Mother Cabrini’s Paper Boat Monument

The point is to feel the after-image of Wagner’s harmony in your body without actively playing it. A way of closing the January loop without resolving it completely. Because the whole year is still ahead, and the Dutchman’s curse is the prologue for everything else you’re going to walk.

Looking out from Wagner Park over New York Harbor towards New Jersey

Robert F. Wagner Park, Battery Park City, looking north

Looking East from Robert F. Wagner Park across New York Harbor to the Statue of Liberty

Nachklang

By the end of January, nothing is resolved. The walk does not conclude the story. It only proves that waiting can be inhabited. The Dutchman does not seek redemption so much as permission to remain. To step ashore briefly, to be seen without being fixed, to continue moving without being lost. This is the quiet lesson of the month: that wandering is not the absence of direction, but the refusal to rush toward one.

The city, in winter, understands this. Ferries run. Streets empty. The horizon remains visible. New York becomes less declarative, more tidal. You learn to listen for repetition rather than progress. For return instead of arrival. When January ends, the sea recedes but does not disappear. The weather shifts. The body re-enters the crowd. Something human waits ahead. Impatient, judgmental, desirous of rules and reasons.

But for now, the vessel moves on. Not cured. Not finished. Still underway.

What’s Next for February

If Der Fliegende Holländer is about being trapped in repetition, condemned to circle, return, and depart without rest, then Tannhäuser begins where January leaves off. With the dangerous belief that escape is possible. February turns inland, away from the harbor and toward temptation, conflict, and divided allegiance. Where the Dutchman is cursed by time, Tannhäuser is torn by desire. Between sensual immersion and moral order, between indulgence and absolution, between worlds that refuse reconciliation.

The walk which follows does not leave repetition behind. It complicates it. The question shifts from How do I endure the loop? to Which world do I belong to, and what do I sacrifice by choosing? January ends at the edge of the city, listening to unresolved water. February begins with the far more dangerous proposition. That resolution might be demanded.