Ghost Ships, Green Lights: Januar mit Der Fliegende Holländer

There are two kinds of wellness that get discussed in the modern city. The first is the kind you can buy. Supplements, memberships, optimizations, the glossy promise that you can hack your body into equilibrium. The second is quieter, older, and far harder to engineer. The kind you can anticipate. The kind that starts at 8am, not because your morning is filled with joy, but because your day contains a hinge. A turning point. A small, private appointment with meaning.

That has been January for me. Not merely doing something after work, but living with a tether out in front of the day. Something to walk toward, something which pulls. Arriving in the office early, leaving around 3pm, and stepping out into New York with a mission has been, in the most literal sense, life-giving. It is astonishing how quickly a workday changes when it is no longer a sealed container. When it is punctured, deliberately, by the promise of a ferry wake, a harbor wind, a particular bar of music waiting at the edge of the afternoon.

This is the positive psychology of the itinerary. Not the pleasure of the thing itself, but the vitality of looking forward. Anticipation as a form of nourishment. It creates a future you can feel in your body, and one of the most underrated forms of agency. It’s easy, in adult life, to become a person who primarily reacts. To emails, to meetings, to the urgent present. But a planned walk through the city, especially one paired with a work as vast and haunted as Der Fliegende Holländer, turns you back into someone who initiates. Someone who chooses an experience, then moves toward it. That motion matters. It is the difference between being carried by the current and picking up an oar.

And then there is the music itself. Wagner does not simply accompany the city. He changes its weather. Listening consistently to Holländer while traveling through New York has been transportative in the old, serious sense of the word. It has carried me. The South Street Seaport becomes less a neighborhood and more a threshold. The Staten Island Ferry becomes less public transit and more ritual. The same water I have passed a hundred times becomes newly saturated with romance, dread, tenderness, and a kind of yearning so concentrated it feels like a physical element, like mist.

I’ve been falling in love with the city again after a long time, and I don’t mean that lightly. Cities, like relationships, often dull through repetition. You can still appreciate them, still respect them, still function inside them. Yet with age the original voltage fades. What Wagner has done this month is restore the spark. He has returned New York to me as a place capable of myth. Not in a silly cosplay sense, but in the deeper sense. A city as an instrument you can play with attention.

There is a particular memory which keeps resurfacing, the way certain images do when they become not just recollections but symbols. Senta’s ballad on the Staten Island Ferry. Seagulls following the boat across the harbor, riding the air in our wake. It felt, in the moment, like they were on the journey with me. Companions, witnesses, maybe even messengers. That is the kind of detail your rational mind dismisses until your deeper mind refuses to let it go. Because what I actually experienced was an alignment. Music, motion, weather, and animal life briefly converging into one coherent frame.

Wagner is often accused, sometimes fairly, of excess. Too much sound, too much longing, too much metaphysics. But what I found on that ferry is that excess is precisely what the modern day has been draining from us. We live in an era of compression. Short messages, short attention, short patience, short everything. Wagner’s long line does the opposite. It stretches time. It insists that a feeling can be sustained, not just sampled. And when time stretches, the world opens up. The seagulls become part of the score. The harbor becomes a stage. Even the cold becomes expressive, a kind of involuntary participation.

This is where Gatsby arrived in my thoughts, not as a literary flex, but as a recognition. “Gatsby believed in the green light,” Fitzgerald writes, “the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us.” The line is famously about desire, illusion, the relentless human tendency to reach beyond what is reachable. But this month, it has landed differently. The green light isn’t just longing. It’s the mechanism by which we keep moving. It recedes, yes. It eludes, yes. But it also organizes the will. “So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.” It’s impossible not to read that line on the water without feeling it in your bones.

Because the harbor is where the metaphor becomes literal. Water carries you forward while quietly reminding you that everything is also behind you. You move, but the wake proves you were somewhere else a moment ago. And in January, that wake has felt thick with ghosts.

Walking through Robert Wagner Park in bitter cold, looking out at the Statue of Liberty, I felt the romance of the water intensely. Not a tourist romance, but something older and darker. The sense of passage. Of all the lives that moved through that corridor. Arrivals, departures, exiles, returns, people who stepped onto these shores with nothing but hope and fear and a name that might change spelling at the next desk. The rain and cold didn’t ruin the experience. They made it honest. They reminded me that arrival is not always warm. That the city has always demanded something of those who come to it.

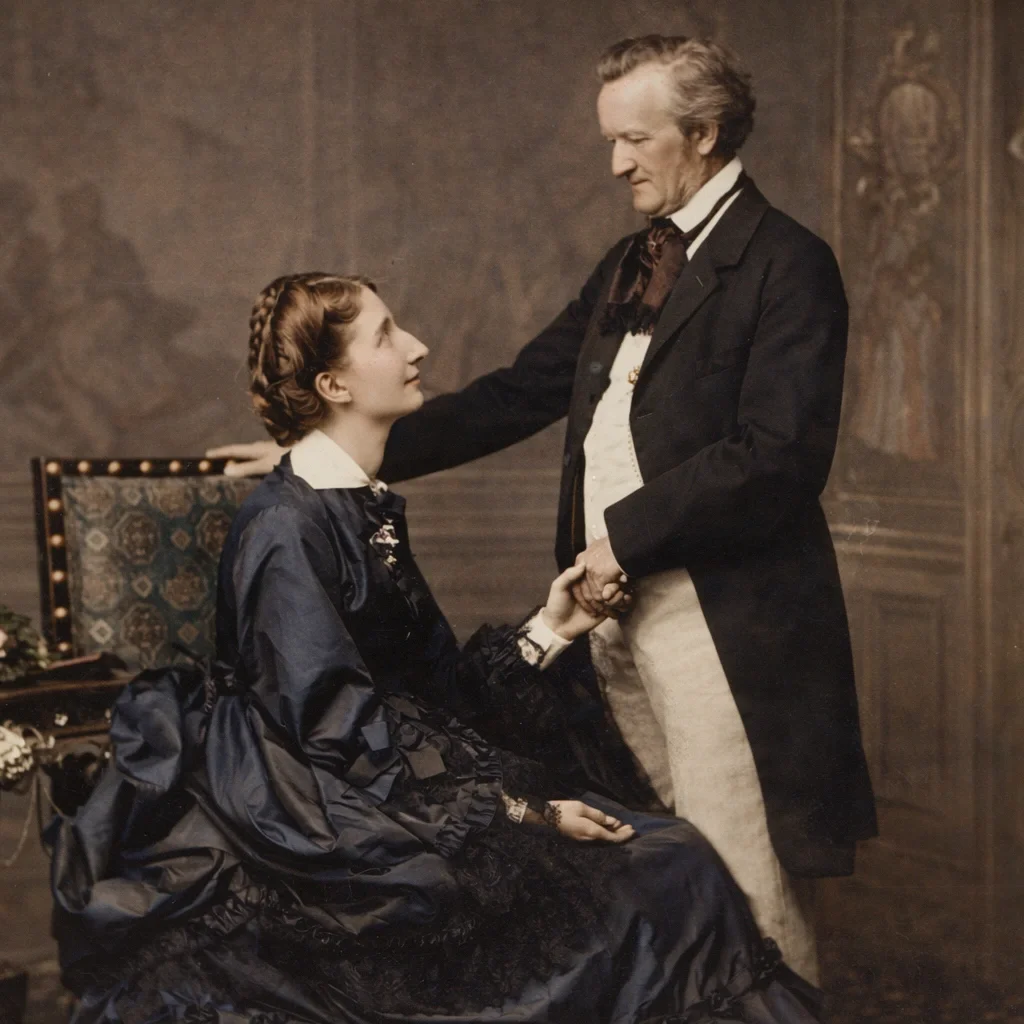

And then 12 Old Slip. A tower of glass and steel now. Efficient, modern, almost aggressively present tense. And yet I stood there feeling Wesendonck’s presence. Not as a mystical visitation, but as a sudden awareness of transatlantic continuity. A thread pulled taut across time. Nineteenth-century Germany, Wagner’s inner life, the intimate social networks which helped make his work possible, and then this cold New York air almost two hundred years later. The thought that a call was sent and never heard. Or perhaps it was heard, but only faintly, and only by those willing to train their ears.

That’s what this project is doing, really. It is training my ears to hear calls that modern life makes easy to miss. Not only Wagner’s calls, but the city’s. The harbor speaks. The ferry speaks. The buildings speak. They speak in the language of history and repetition and return. “Ghost ships abound,” I wrote in my mind as I walked, and it felt true in more than one register. The Dutchman’s ship is the obvious ghost ship. Cursed, condemned to reappear, always arriving too late, always leaving too soon. But the ferry’s wake is also the wake of immigration. It’s the trace of millions of crossings, documented and undocumented, celebrated and mourned. It’s the reminder that the harbor is not merely scenery. It is an engine of human change.

And so I hear Senta calling out to the Dutchman while quietly walking the harbor’s edge alone. I hear devotion calling out to despair. I hear the human willingness, sometimes reckless, sometimes noble, to bind oneself to an idea of redemption. Senta is absurd and magnificent at once. The person who believes that love can redeem a curse. Whether that is naive or courageous depends on your mood, your history, and the hour of the day you are listening. On the ferry, with seagulls in formation and the city dissolving into rain, it felt less like a plot device and more like a mirror.

Because I, too, am living in a world between my ears. Invented and realized by Wagner, but lived in real experience across an ocean and across time. That’s the part I didn’t anticipate at the beginning of January. I assumed I would be “pairing opera with locations,” like a clever personal curriculum. What happened instead is that the locations began to enter the opera, and the opera began to enter the locations. The boundary dissolved. Art stopped being something I consumed and became something I inhabited.

This is what it means, I think, to fall in love with a city again. Not to discover new restaurants (though I have been greatly enjoying exploring New York’s German food), not to accumulate new experiences like souvenirs, but to re-perceive what was already there. To move through familiar streets with a different instrument playing inside you. To let the afternoon become a kind of second life. One which is not an escape from work, but a rescue of the self from pure productivity.

The project is called Ein Wanderwerk in zwölf Aufzügen, but January has already taught me what wanderwork truly means. The work is not just the writing or the itinerary. The work is the cultivation of a mind capable of being moved. The work is keeping a green light out in front of the day, not because you’ll ever fully reach it, but because reaching toward it makes you more alive. The work is consenting to be haunted. By music, by history, by water, by the idea that a call can travel farther than the caller ever imagined.

And one fine morning, maybe not in the morning at all, maybe at 3pm in winter rain, you look up and realize the city is singing back.