Condemned to the Crossing: Werner Herzog and the Curse of the Flying Dutchman

There is a particular kind of motion which recurs obsessively in Werner Herzog’s cinema. Forward movement without arrival. Boats push upriver against impossible currents. Men haul ships over mountains only to find that the mountain was never the point. Journeys unfold not toward redemption but toward exposure. This is why Herzog is so often misread as a chronicler of madness or obsession. He is something colder and more precise. Herzog films the metaphysics of compulsion. And in this, he stands closer to Wagner’s The Flying Dutchman than to any romantic tradition of adventure.

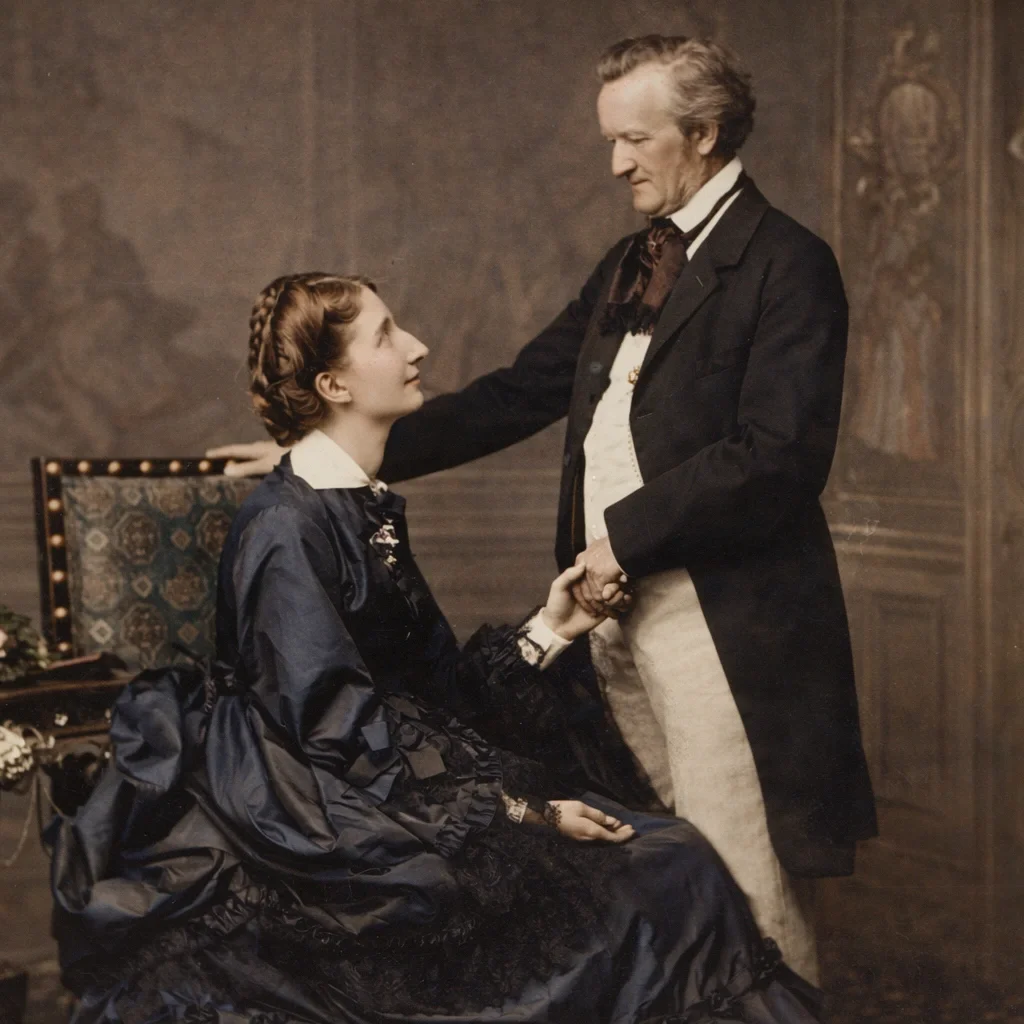

The Flying Dutchman is Wagner’s first fully formed statement of a worldview that will haunt his later work. That there are states of being so overdetermined by will, pride, or defiance that they can no longer return to ordinary time. The Dutchman is not punished for sin in any conventional moral sense. He is punished for absolutism. He makes a vow that admits no contingency, no humility, no accommodation with the world’s limits. His curse is not eternal sailing per se; it is eternal repetition. He is allowed to land, but never to belong. He may encounter others, but never to remain among them. Movement becomes his prison.

This is the core Herzogian condition.

Herzog’s protagonists are rarely rebels against society in a political sense. They are rebels against finitude. They refuse the modest agreements which allow life to proceed imperfectly. Like the Dutchman, they demand terms the world cannot honor. And like the Dutchman, they are not annihilated for this demand. They are preserved within it, condemned to act it out again and again.

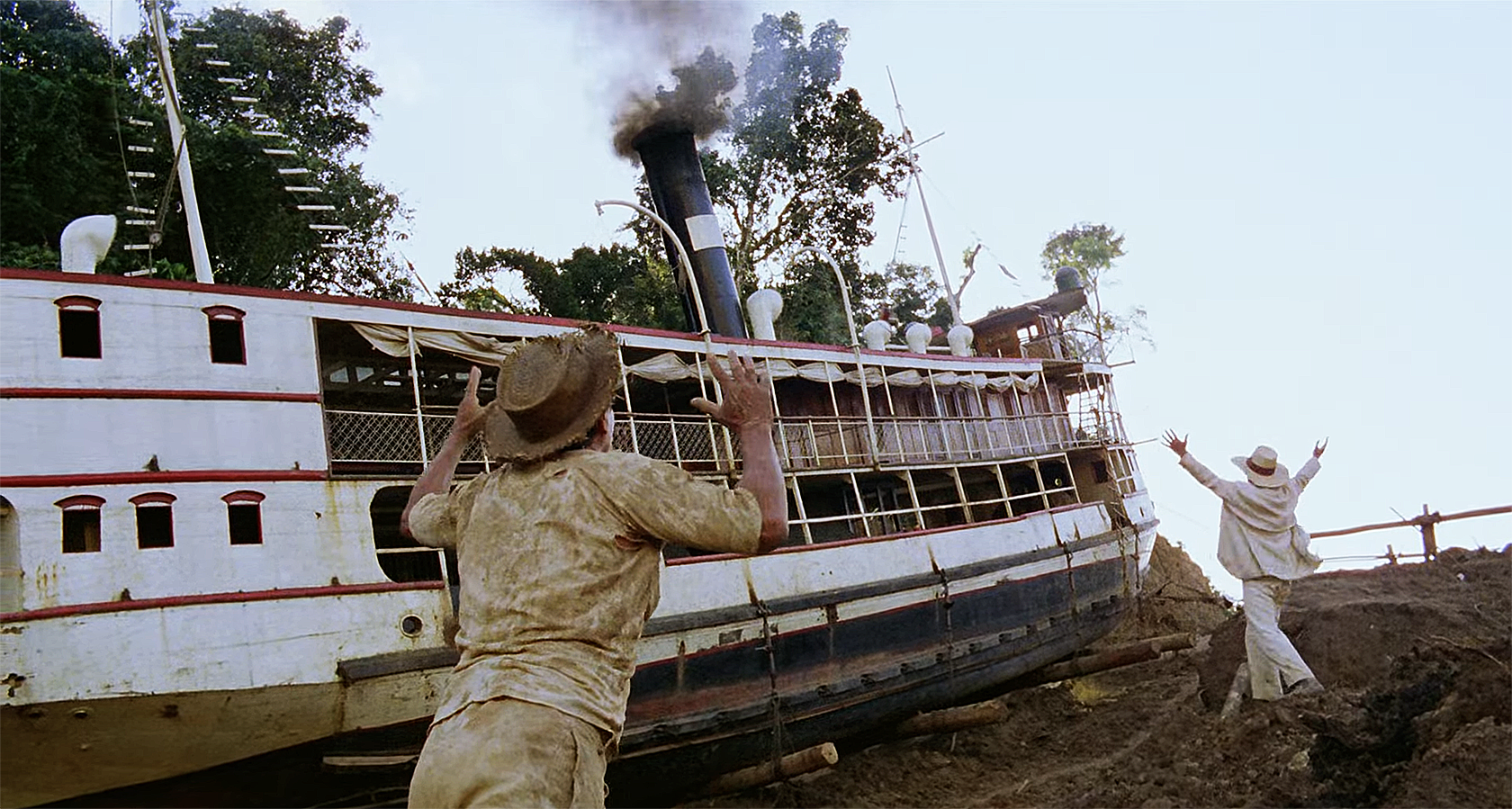

Consider Herzog’s Aguirre, the Wrath of God. Aguirre’s descent into the Amazon is not a journey of conquest but a slow stripping away of temporal coherence. The river does not oppose him dramatically. It absorbs him. Aguirre’s madness is not excess emotion but narrowed focus. He clings to an idea of destiny so pure that it annihilates context. By the end, he is literally afloat among corpses, still declaring empire to no one. This is the Flying Dutchman without the sea. A man severed from reciprocity, condemned to motion as assertion.

Wagner’s Dutchman suffers not because he sails endlessly, but because he cannot stop believing in the salvific power of a single condition. Once every seven years, he may come ashore if he can find a woman faithful unto death. This clause is crucial. The Dutchman does not seek love as relationship. He seeks love as absolution. Senta, like so many Wagnerian figures, is less a person than a wager. Can the world produce something absolute enough to redeem an absolute vow?

Herzog returns to this structure relentlessly. Fitzcarraldo is the most explicit Flying Dutchman narrative ever committed to film without naming itself as such. Fitzcarraldo’s dream of bringing opera to the jungle is often framed as quixotic idealism. But the real drama lies elsewhere. Fitzcarraldo does not want to build an opera house. He wants to prove that will itself can reorder reality. The hauling of the ship over the mountain is not instrumental. It is sacramental. Like the Dutchman’s eternal sailing, the act becomes its own justification.

What makes Fitzcarraldo so deeply Wagnerian is that the opera he loves, Caruso’s voice, European transcendence, is not a civilizing force. It is a private myth. It does not connect him to others; it isolates him. The indigenous laborers are not collaborators in his dream. They are vectors through which the dream temporarily manifests. Once again, Herzog films a man who mistakes intensity for meaning, and motion for progress.

Herzog understands something Wagner grasped early. That damnation does not require hell. It requires only a closed system of belief. The Dutchman’s curse is elegant because it is internally coherent. He does not suffer randomly. He suffers logically. He lives inside the consequences of his own vow.

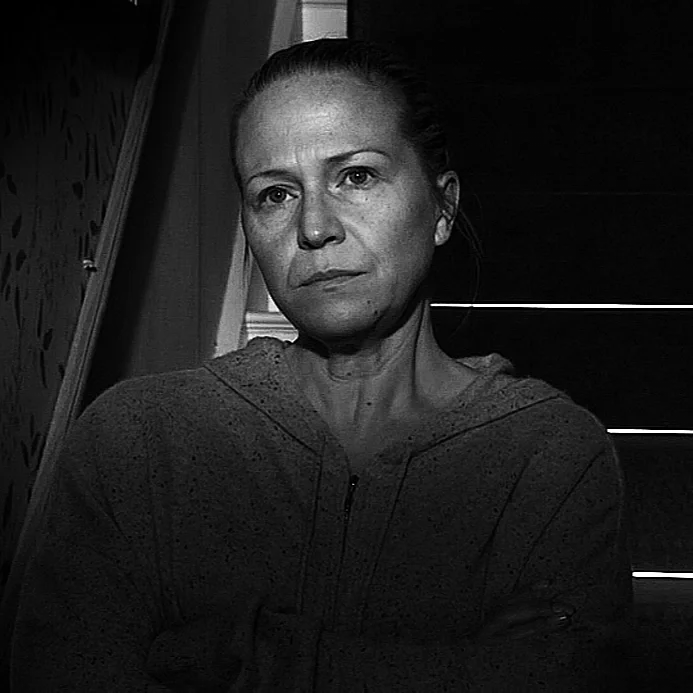

This logic extends into Herzog’s more overtly mythic works. Nosferatu the Vampyre is explicitly maritime, explicitly cursed, explicitly condemned to repetition. Herzog’s Dracula is not seductive; he is exhausted. He longs not for domination but for termination. He is the Dutchman who has lost even the illusion of possible redemption. Eternity, here, is not grandeur. It is administrative continuity without hope.

This is where Herzog diverges sharply from romanticism. His films are not celebrations of obsession. They are forensic examinations of it. Herzog does not admire the Dutchman’s defiance. He documents its cost. The world Herzog films is indifferent not in a nihilistic sense, but in a geological one. It does not argue with the obsessed. It simply outlasts them.

Wagner’s sea functions similarly. The ocean in The Flying Dutchman is not a metaphor for chaos. It is order without mercy. It keeps time better than humans do. It remembers vows long after the speaker has forgotten why they were made. The Dutchman’s tragedy is not that the world rejects him. It is that the world takes him at his word.

This is why redemption in The Flying Dutchman is so unstable, so troubling. Senta’s self-sacrifice is often staged as triumph, but Wagner himself was never fully at ease with it. Is Senta’s leap an act of love, or an absorption into the Dutchman’s curse? Does redemption arrive, or does the system merely complete itself? Wagner will wrestle with this ambiguity for the rest of his career.

Herzog refuses the question entirely. Redemption, in his films, is either deferred indefinitely or revealed as another illusion of control. There is no Senta in Herzog’s world because there is no faith that another person can absolve your metaphysical posture. Herzog’s ethic is harsher than Wagner’s early romanticism, but it grows from the same root: the belief that the universe does not negotiate with absolutes.

Across Herzog’s oeuvre, movement becomes a moral condition. Those who accept limitation. Those who stop, who listen, who adapt, may suffer, but they remain human. Those who refuse limitation become spectral. They drift through landscapes like ghosts, visible but untethered. They are no longer fully alive, but not allowed to disappear.

This is the deepest connection between Herzog and The Flying Dutchman. Both are studies in the cost of refusing return. Not return as retreat, but return as participation in shared time. The Dutchman cannot return to ordinary life because he has structured his existence around exception. Herzog’s protagonists do the same. They place themselves outside the ordinary contracts of patience, compromise, and reciprocity, and are astonished when the world responds by leaving them there.

Herzog once spoke of an ecstatic truth deeper than factual accuracy. That phrase is often misunderstood as an endorsement of myth over reality. In fact, it is closer to Wagner’s insight in The Flying Dutchman. That certain truths emerge only when human will collides with indifferent systems. Ecstatic truth is not comfort. It is exposure.

In the end, the Flying Dutchman does not need the sea, and Herzog does not need ships. What matters is the structure. A being who has bound himself to motion as proof of meaning, and who discovers too late that motion without humility is indistinguishable from stasis. Herzog films that discovery again and again, with relentless clarity.

The curse is not eternal wandering. The curse is the inability to stop wandering without ceasing to know who you are.