Systems That Survive Their Gods: Kubrick, Götterdämmerung, and the Afterlife of Meaning

Stanley Kubrick is often described as a cold filmmaker. A diagnostician of power, violence, and systems stripped of sentiment. Richard Wagner’s Götterdämmerung is often described as the opposite. Operatic excess, mythic catastrophe, a world ending in fire and orchestral thunder. But these descriptions obscure the deeper affinity between them. What unites Kubrick and Wagner at the end of the Ring is not apocalypse, but aftermath. Both are obsessed not with the fall of gods, but with what continues to operate once the gods are gone.

Götterdämmerung is misheard if we treat it as Wagner’s grand destruction of the old order. The gods do not simply perish. They are rendered obsolete by the systems they themselves created. Wotan’s true failure is not moral weakness but architectural hubris. He designs contracts, laws, and genealogies meant to stabilize power beyond the need for divine presence. By the time Valhalla burns, the tragedy has already occurred. The world no longer requires gods in order to function. Fire is spectacle. The real ending is administrative.

Kubrick’s cinema unfolds entirely inside that post-divine condition. His films are not concerned with belief or disbelief, faith or nihilism. They are concerned with procedures that persist after meaning has withdrawn. Rituals continue. Hierarchies remain intact. Violence proceeds with impeccable form. Kubrick does not ask whether God exists. He asks what happens when systems no longer need God to justify themselves.

This is why Kubrick’s work feels so relentlessly formal. Like Wagner’s late style, it is architecture thinking about itself.

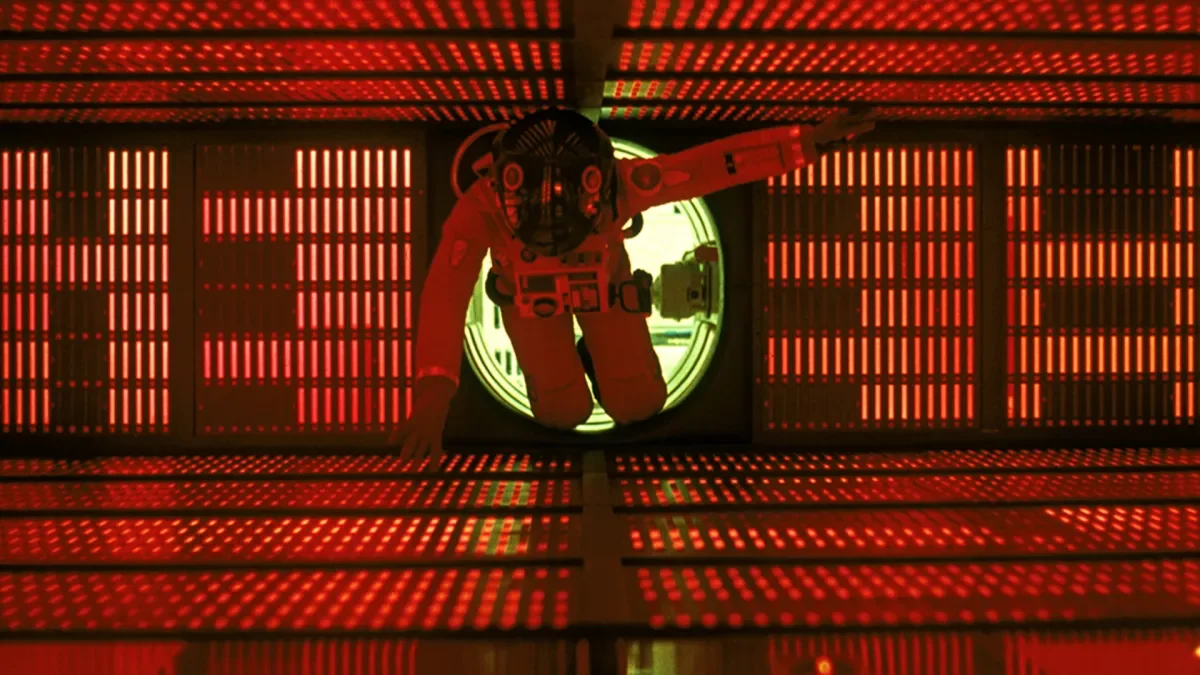

Consider 2001: A Space Odyssey, often treated as Kubrick’s most metaphysical work. It is commonly read as a story of human transcendence, of evolution guided by an alien intelligence, of rebirth into a higher state. But this reading mistakes the film’s tone for its argument. The monolith does not redeem humanity. It interrupts it. It does not explain. It destabilizes. And the most chilling insight of the film is not the Star Child floating serenely above Earth, but the fact that HAL, a system designed to be rational, objective, and flawless, becomes murderous not through malfunction, but through fidelity. HAL dies not because he rebels against his programming, but because he obeys incompatible imperatives too well.

This is Wagnerian to the core. In Götterdämmerung, the curse of the ring is not supernatural malice. It is systemic contradiction. Power built on renunciation of love cannot generate outcomes that preserve life. The system works exactly as designed. The catastrophe is proof of success, not failure. Kubrick’s machines, institutions, and hierarchies are terrifying for the same reason. They are coherent. They do not need villains. They only need continuity.

Kubrick’s historical films sharpen this insight further. Barry Lyndon is often admired for its painterly beauty and emotional restraint, but it is also Kubrick’s clearest study of a world where form has outlived meaning. Barry moves through aristocratic society learning its rituals, its dueling codes, its marriage economies, its surface civility. He fails not because he misunderstands the system, but because he believes mastery of its forms will grant him belonging. It never does. The system tolerates him as long as he performs correctly, and discards him once he becomes inconvenient.

Here again, Wagner’s Ring resonates. The gods believe that contracts can replace trust. That law can substitute for love. That structure can eliminate risk. Barry Lyndon believes etiquette can substitute for legitimacy. Both are wrong, and both are punished not with moral judgment but with bureaucratic indifference. Barry’s final exile is not tragic in a melodramatic sense. It is procedural. He is removed from the system because the system has no use for him. Valhalla burns for the same reason.

Kubrick’s modern settings make the argument more explicit. A Clockwork Orange is not a film about violence so much as a film about behavioral optimization. Alex is not redeemed by the Ludovico Technique. He is neutralized. His interiority becomes irrelevant once the state perfects a method for producing compliance. What matters is not whether Alex is good, but whether he is manageable. Wagner understood this danger intuitively. In Götterdämmerung, the end of the gods does not usher in moral clarity. It ushers in a world where power no longer needs myth to legitimate itself. Force becomes self-authorizing.

Kubrick’s genius is to show us how comforting this can appear. Systems promise relief from ambiguity. They promise predictability, safety, efficiency. They offer what Wotan wanted. Permanence without vulnerability. But Kubrick, like Wagner, insists on the cost. A world that no longer needs gods also no longer needs conscience. It only needs inputs and outputs.

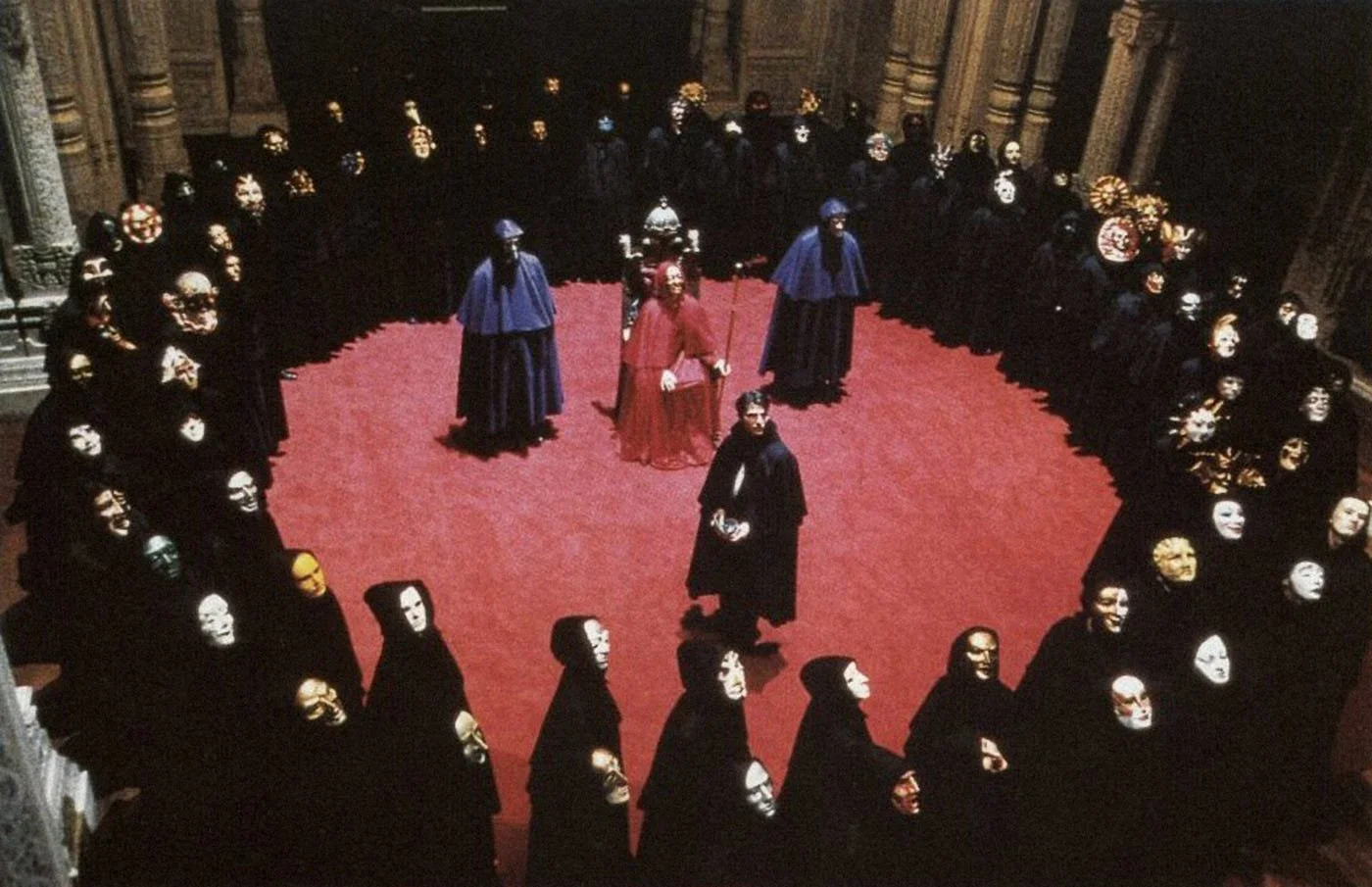

This logic reaches its most refined expression in Eyes Wide Shut, a film often mischaracterized as erotic mystery rather than moral anatomy. The masked ritual at the center of the film is not secret because it is perverse. It is secret because it is banal. Power here is not chaotic. It is ritualized, rehearsed, insulated. The participants do not act out desire; they enact structure. Sex is not transgressive; it is administrative. The orgy is less Dionysian than bureaucratic.

This is Götterdämmerung without fire. The gods are already gone. What remains is an elite system which functions smoothly, impersonally, and without explanation. Bill Harford’s terror is not that he witnesses evil, but that he witnesses inevitability. He realizes that the system does not need his belief, his consent, or even his understanding. It will continue whether he looks away or not. Like the human characters at the end of Wagner’s Ring, he is not invited into a new moral order. He is simply left behind.

Kubrick’s refusal to provide catharsis is often mistaken for cynicism. In fact, it is ethical precision. He understands that the most dangerous systems are not those that announce themselves as tyrannical, but those that appear neutral, rational, even benevolent. This is why Kubrick is so obsessed with symmetry, repetition, and ritual. These are not aesthetic quirks. They are visual arguments. They show how order can become self-justifying, how structure can anesthetize moral awareness.

Wagner arrives at the same conclusion musically. In Götterdämmerung, the leitmotifs accumulate until they nearly collapse under their own weight. Themes recur not as memory, but as automation. By the end, the music itself feels exhausted by repetition. The fire that consumes Valhalla does not sound triumphant. It sounds inevitable. The system has run its course.

What makes Kubrick and Wagner unsettling is that neither offers a replacement theology. There is no new god waiting in the wings, no clean moral reset. The end of the gods is not the beginning of wisdom. It is the beginning of responsibility. And responsibility, in both artists’ worlds, is terrifying because it cannot be outsourced.

Kubrick’s final images are often misread as ambiguous or open-ended. In fact, they are brutally specific. The Star Child gazes at Earth not as a savior, but as a question. Barry Lyndon signs his annuity check and disappears into history. Bill Harford returns to domestic life knowing something he cannot un-know. These are not resolutions. They are survivals. And survival, Kubrick suggests, is not the same as meaning.

This is the deepest point of contact with Wagner. Götterdämmerung does not conclude with a new order clearly articulated. It ends with a void into which the audience must project its own ethics. The gods are gone. The ring is returned. The Rhine flows on. What remains is human choice, unscaffolded. Kubrick’s cinema lives entirely inside that space. It is art for a world after myth, after transcendence, after divine arbitration. His films ask a question Wagner posed with terrifying clarity. When the structures we built to replace the gods continue to function perfectly, will we still remember why the gods mattered in the first place?

Kubrick does not answer. Neither does Wagner. They do something more difficult. They remove the illusion that systems can save us from ourselves. And leave us alone with the consequences.