Love Without Distance: Tristan, Solaris, and the Violence of Fulfilled Desire

There is a persistent temptation, when placing Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde alongside Tarkovsky’s Solaris, to describe both works as meditations on love which transcends death. This is true, but it is also dangerously incomplete. What Wagner and Tarkovsky are really staging is not transcendence but collapse. The breakdown of the psychic, ethical, and temporal structures that normally allow love to remain human. In both works, love does not redeem by enduring; it annihilates by fulfilling itself too completely. The catastrophe is not that love is impossible, but that it becomes total.

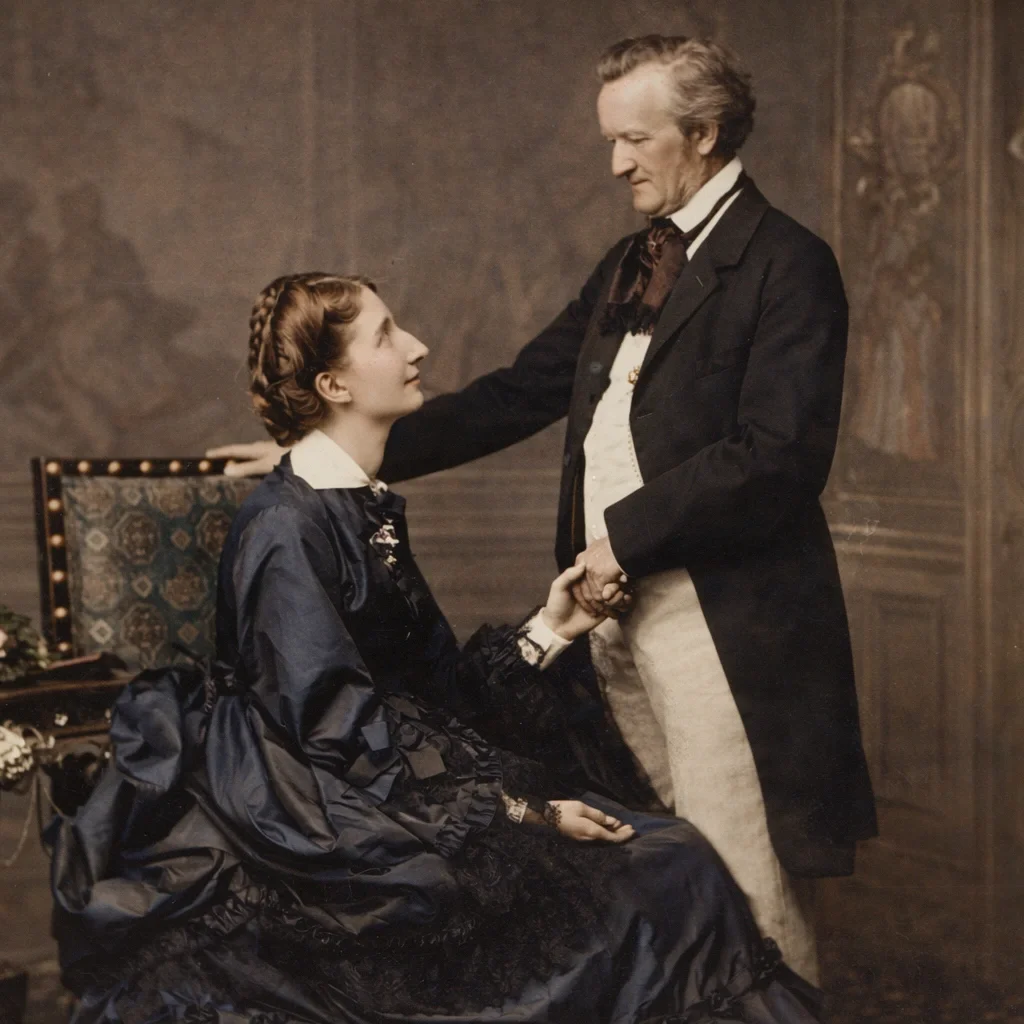

Wagner understood earlier than most that desire is not inherently tragic. What makes desire tragic is the erasure of distance. Tristan und Isolde is often described as a love story poisoned by circumstance, but Wagner’s music insists on something more radical. The lovers are undone not because the world forbids their union, but because their union abolishes the world. The love potion does not create love; it removes mediation. It collapses the boundary between inner longing and external reality, leaving no space for narrative, duty, or time itself. Once desire is no longer delayed, shaped, or resisted, it becomes infinite. And lethal.

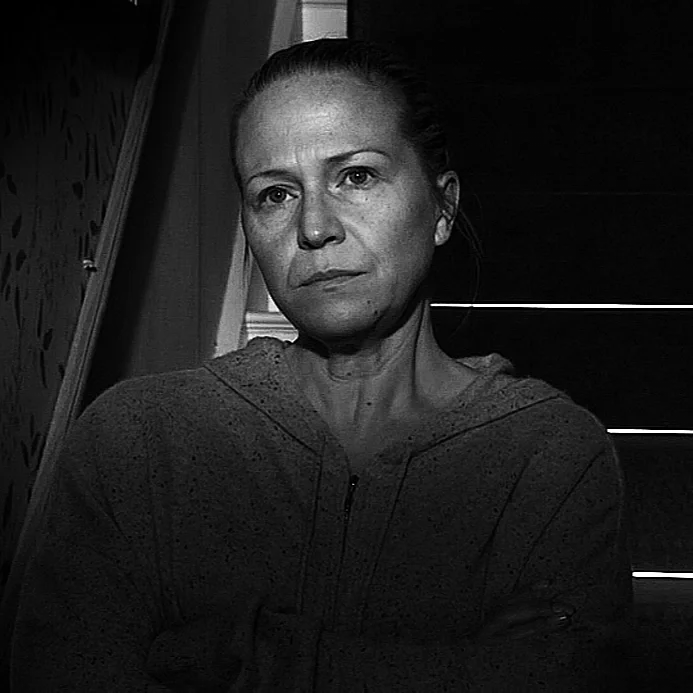

Tarkovsky’s Solaris conducts the same experiment in a different register. The Solaris ocean does not judge, punish, or moralize. It simply responds. It manifests what lies beneath conscious intention, translating memory and guilt directly into physical presence. Kelvin’s resurrected wife is not a ghost, nor a hallucination, nor a miracle in any consoling sense. She is desire without distance. Love returned without consent, without finitude, without the merciful filtering of time.

This is the central and underappreciated link between Wagner and Tarkovsky. Both reject the comforting fantasy that love becomes purer when unbounded. Instead, they ask whether love can survive its own realization. Their answer, in both cases, is devastatingly consistent: love without limits ceases to be love at all. It becomes ontology.

In Tristan, Wagner engineers this insight musically. The famous unresolved harmonies are not expressive ornamentation. They are structural sabotage. Resolution is endlessly deferred because resolution would mean closure, and closure would reintroduce the world. The music insists on suspension, on perpetual reaching, on a state in which desire is never allowed to crystallize into satisfaction. This is not romantic indulgence. It is psychological extremity. Wagner forces the listener into the lovers’ condition. A longing so absolute that it cannot coexist with daylight, language, or social order. The lovers do not die because they are punished. They die because there is nowhere left to live.

Solaris enacts the same logic through narrative restraint. Tarkovsky refuses the conventions of science fiction explanation not out of obscurantism, but because explanation itself would function as a limit. To explain Solaris would be to domesticate it, to turn it into a system with edges. Instead, the planet remains radically other. A mirror that does not reflect appearances but essences. The visitors it produces are not wish-fulfillments but exposures. They confront the human characters with the difference between who they think they are and what they actually desire when stripped of moral performance.

Kelvin’s tragedy is not that Harey returns, but that she returns without resistance. She loves him absolutely, instinctively, without memory of betrayal or the slow erosion of intimacy that once made their relationship human. Like Isolde under the potion’s influence, Harey is love without history. And it is history, shared time, shared disappointment, shared negotiation, that gives love its ethical dimension. Without it, love becomes a closed circuit, endlessly self-reinforcing, intolerant of the world beyond itself.

This is why both works frame love as nocturnal. In Tristan, night is not merely a romantic setting. It is a metaphysical condition. Night is the realm where distinctions dissolve, where social roles vanish, where the lovers can exist without mediation. Day, by contrast, is the realm of differentiation. Duty, language, consequence. Tristan and Isolde do not long for death because they are suicidal. They long for a state in which the daylight world no longer interrupts the totality of their desire. Death becomes attractive not as annihilation, but as permanence.

Solaris reproduces this dynamic spatially rather than temporally. Earth represents the daylight world. Bureaucratic, procedural, structured by explanation and distance. Solaris station is a liminal space, suspended between rational inquiry and existential collapse. The planet itself is pure night, not in darkness but in opacity. It does not communicate. It envelops. It does not clarify. It intensifies. Kelvin is drawn toward remaining there not because it offers happiness, but because it offers an end to negotiation. To stay is to surrender to a love that no longer requires effort, forgiveness, or self-knowledge.

Both Wagner and Tarkovsky recognize this as a temptation rather than a solution. The most important moments in both works are not the ecstatic ones, but the moments when the characters glimpse the cost of what they are experiencing. Tristan’s flashes of lucidity, his awareness that day must come, that the world cannot be abolished without consequence, mirror Harey’s growing recognition that her existence is a violation rather than a gift. Harey’s suicide is often misread as a gesture of despair. In fact, it is an ethical act. She chooses finitude. She chooses to reintroduce absence as a form of love.

This is one of Tarkovsky’s most Wagnerian insights. Redemption, if it exists, does not come from fulfilling desire, but from restoring distance. Harey’s final act reinstates the boundary that makes love meaningful. It echoes Isolde’s Liebestod, which is frequently mischaracterized as an apotheosis of love when it is actually Wagner’s acknowledgment that love cannot be sustained in the world it has tried to abolish. The transcendence is not triumphant. It is terminal.

What makes this mapping especially powerful is how it reframes Tarkovsky’s broader concerns. Across his work, Tarkovsky is deeply suspicious of immediacy. He distrusts technologies, ideologies, and emotional states that promise unmediated access to truth or fulfillment. Solaris is not dangerous because it lies, but because it tells the truth too directly. It bypasses the slow, painful, human processes by which meaning is normally assembled. Like Wagner, Tarkovsky understands that suffering is not merely something to be eliminated. It is a structuring condition of consciousness. Remove it entirely, and you do not arrive at peace. You arrive at incoherence.

This places Solaris in a direct lineage with Tristan rather than with science fiction more broadly. Both works are warnings disguised as love stories. They seduce the audience into empathizing with desire at its most absolute, then reveal, without sermonizing, that such desire is incompatible with life as a shared, temporal, ethical enterprise. Love that refuses limits ultimately refuses the otherness of the other. It consumes rather than encounters.

Seen this way, the Solaris ocean functions as a cosmic love potion. It does not force anyone to love. It removes the safeguards that prevent love from becoming annihilating. And like the potion, it exposes a truth that is difficult to accept. That much of what we call love depends on not having exactly what we want. Distance is not the enemy of intimacy. It is its precondition.

Wagner arrived at this insight musically, through harmonic instability and deferred resolution. Tarkovsky arrives at it cinematically, through duration, silence, and refusal of explanation. Both insist that meaning emerges not from intensity alone, but from form. And form, by definition, requires limits.

In the end, Tristan und Isolde and Solaris do not ask whether love can conquer death. They ask a more unsettling question. Whether love that conquers death would still be love, or whether it would become something colder, heavier, and less human than loss. Their shared answer is uncompromising. Love must remain unfinished to remain humane. The moment it closes in on itself completely, the world disappears. And with it, the very conditions that made love worth longing for in the first place.