Democracy’s Invisible Infrastructure: On Civic Imagination and the Failure of Rienzi

November’s Rienzi arrives in the Aufbruch project at a peculiar moment in the cycle, after the long Wagnerian descent through myth, renunciation, and collapse, and just before the calendar turns toward its quieter, more ambiguous close. On the surface, it appears to be an opera about politics, demagoguery, and the volatility of crowds. That reading is accurate but incomplete. What Rienzi ultimately exposes, and what the Aufbruch project, perhaps without yet naming it, is uniquely positioned to reveal, is that the real site of civic strength or failure is not the public square itself, but the shared imaginative space that precedes and survives it. Democracies do not endure because people gather. They endure because people imagine together. When that capacity erodes, gatherings become theatrical rather than constitutive, and institutions persist only as hollow forms.

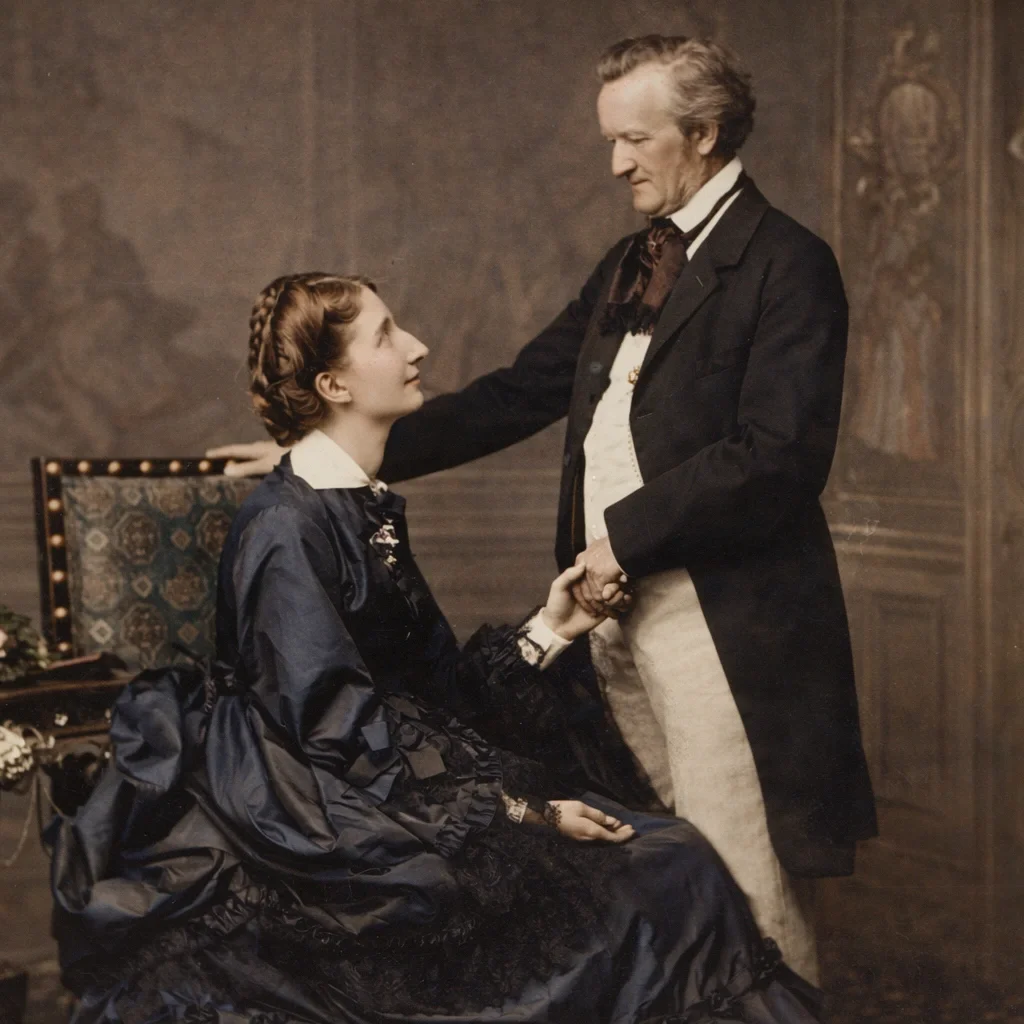

Wagner’s early opera is often dismissed as bombastic, immature, or overly literal in its politics. Yet its dramatic excess is precisely what makes it useful here. Rienzi’s Rome is not a realistic polity. It is an interior one, a projection of collective longing, grievance, memory, and hope. The choruses are not background color but the true protagonists of the work, because they represent the fluctuating imaginative consensus that allows authority to appear legitimate one moment and intolerable the next. Rienzi himself is less a character than a vessel through which the crowd rehearses its own aspirations. His rise is not caused by persuasion alone but by receptivity. Something in the civic imagination of Rome is already primed to hear him.

This is where November’s walk through New York’s civic spaces becomes more than symbolic pairing. City Hall Park, the steps of courthouses, the wide openness of Union Square. These are not merely locations where politics occurs. They are physical invitations to imagine oneself as part of a collective story. Their power does not lie in their architecture alone but in the accumulated narratives that cling to them. Assemblies remembered, marches reenacted, voices echoed forward through time. When you stand in such a place, you are not only occupying space; you are entering an interpretive field shaped by expectation and memory. The Aufbruch project treats this not as nostalgia but as practice. It trains attention toward the ways cities quietly teach us what kind of participation is possible.

The critical argument which emerges from Rienzi, and from November’s placement in the calendar, is that civic breakdown rarely begins with institutional failure. It begins with imaginative disintegration. Before trust collapses, meaning does. Before laws are rejected, the stories that justify them lose coherence. Rienzi’s tragedy is not simply that he overreaches or that the crowd betrays him. It is that the shared narrative that once animated both leader and people fragments under its own contradictions. The crowd does not merely turn against him; it loses faith in the very idea that collective voice can be stable or trustworthy. What follows is not revolution but exhaustion.

This insight matters because it reframes contemporary anxieties about polarization, disengagement, and democratic fragility. We often diagnose these conditions in structural terms. Media systems, economic incentives, institutional design, without attending to the deeper layer beneath them. Structures fail more readily when the imaginative ground that supports them has already eroded. When citizens no longer share even a provisional sense of what public life is for, participation becomes performative rather than generative. Crowds still assemble, but they do not cohere. Speech still circulates, but it does not bind.

Rituals, in this context, are not decorative remnants of older political forms but essential scaffolding for civic imagination. Processions, marches, speeches, even the simple act of moving together through a city, function as cognitive and emotional synchronizers. They align attention, calibrate affect, and provide a temporary grammar for collective meaning. Wagner understood this intuitively. His choruses are overwhelming because they dramatize the fragile miracle of alignment: many voices sustaining a single emotional arc. When that alignment breaks, the sound collapses into noise. What remains is not silence but confusion, a vacuum quickly filled by cynicism or withdrawal.

The Aufbruch project implicitly argues that such rituals can be reentered thoughtfully, without nostalgia or naivety. Pairing opera with urban walking is not escapism. It is rehearsal. It allows the participant to experience public space as layered rather than inert, to feel how history, myth, and personal attention intersect in real time. This is a subtle but radical intervention. It suggests that civic renewal does not begin with slogans or platforms, but with the reeducation of perception. One must first relearn how to inhabit shared spaces as meaningful before any durable collective action can follow.

What Rienzi adds to this framework is a cautionary dimension. The crowd lifts you up. The crowd lets you fall. This is not merely a warning about charisma or mass psychology. It is a statement about the volatility of shared imagination when it is unexamined. Collective meaning can amplify hope, but it can also accelerate disillusionment when expectations exceed reality. Democracies falter not only because leaders fail, but because citizens invest their imaginative energy in figures rather than in the slower, less dramatic work of sustaining shared narratives. When those figures inevitably disappoint, the imaginative collapse is total.

November, then, is not about politics as such. It is about endurance. It asks what remains when the procession ends and the voices disperse. The unsettling answer offered by Rienzi is that what remains is often an interpretive void. The city continues, institutions persist, but the sense of common purpose thins. People retreat into private life not because they are apathetic, but because the civic imagination no longer offers a credible story in which their participation matters.

Seen this way, the deeper ambition of what we’re doing here at Aufbruch becomes clearer. It is not a Wagner project, nor a walking project, nor even a cultural diary. It is an attempt to cultivate stronger imaginative literacy. The capacity to recognize, inhabit, and sustain shared meaning over time. This is not a romantic project. It is an infrastructural one. Without imaginative coherence, no amount of procedural correctness can produce legitimacy. Without shared narratives, even well-designed systems feel alien and coercive.

Rienzi matters because it exposes the cost of neglecting this inner architecture. Its failure is not inevitable, but it is instructive. It reminds us that civic life is not held together by force or spectacle, but by a continuously renewed agreement about what is worth doing together. When that agreement frays, the fall is swift, and rebuilding is slow.

In placing Rienzi in November, the Aufbruch calendar quietly reframes the season itself. November is not merely a month of endings or disillusionment. It is a diagnostic interval. It asks what imaginative resources remain once the grand narratives have burned themselves out. The answer is not to abandon public life, but to tend more carefully to the conditions that make it imaginable in the first place. That work is quieter than marches and less visible than speeches, but it is ultimately more durable. It begins not with the crowd, but with the shared inner theatre in which a crowd becomes possible at all.