How Wagner’s Rheingold Decodes Wall Street

A reconstructed spoken narrative

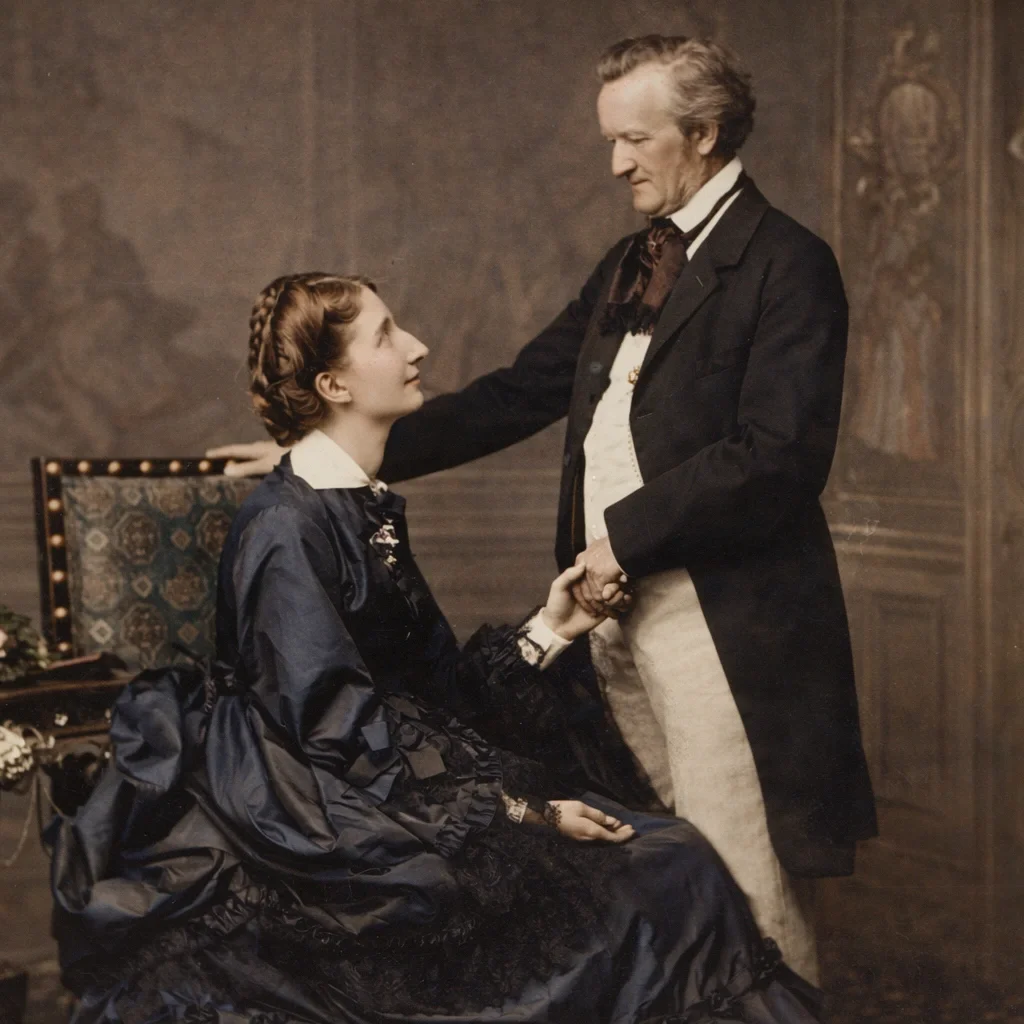

Let me start somewhere unexpected. Not with finance, but with myth. When Richard Wagner opens Das Rheingold, nothing happens. Literally nothing. There’s no melody, no drama, no action. Just a low, sustained E-flat. A sound that feels less like music and more like being. The Rhine before history. Before contracts. Before markets. Before ownership. And that’s important.

Because Rheingold isn’t really about gods or dwarves or magic helmets. It’s about what happens the moment value becomes abstract. The moment something priceless becomes priced. The moment love is renounced in exchange for power. That’s where Wall Street begins too. Alberich, the Nibelung, steals the gold only after being told the price of ownership. He must renounce love. That trade, intimacy for leverage, relationship for control, is the foundational transaction of the modern financial system. Wagner understood this with unsettling clarity.

What’s striking is how contemporary it feels. The gold itself doesn’t do anything. It doesn’t feed anyone. It doesn’t build anything. Its power comes entirely from belief, from consensus. From the shared agreement that this object now stands in for value, for trust, for future promise. That’s not ancient mythology. That’s derivatives. That’s credit. That’s speculative capital. The ring forged from the gold doesn’t create wealth. It concentrates it. And the moment it does, the system destabilizes.

Wotan, the god of contracts, laws, and order, is trapped by his own agreements. He believes he’s in control because everything is written down, signed, formalized. But every contract he makes creates unintended consequences. Sound familiar? Wagner’s great insight is that systems built purely on rules without moral grounding eventually collapse under their own weight. Not because they’re evil, but because they’re brittle. And the giants, Fasolt and Fafner, are perhaps the most tragic figures of all. They build Valhalla, the infrastructure of power, and ask only to be paid fairly. But once the gold enters the system, fairness evaporates. One brother kills the other over the ring. Labor turns on itself. Capital corrodes kinship.

That’s not myth. That’s history. What Wagner is really staging here is the emotional cost of abstraction. When value becomes symbolic, when labor becomes invisible, when wealth becomes detached from human consequence, something essential fractures. The music tells us this before the plot ever does. The harmonies darken. The motion accelerates. What began as stillness becomes anxiety. Wagner doesn’t let us off the hook. The gods know the system is corrupt, and they walk into Valhalla anyway. They choose comfort over correction. They rationalize. They defer. They tell themselves they’ll fix it later.

The opera ends not with triumph, but with denial. Which is why Das Rheingold isn’t an opera about capitalism failing. It’s an opera about how systems fail slowly, politely, beautifully, until the collapse feels inevitable. So when we talk about Wall Street, about markets, about financial systems today, Wagner offers a frame that’s more useful than any balance sheet. He asks what did we trade away to build this? What did we renounce? And who paid the price when value stopped being human-scaled? Because once love is renounced, the bill always comes due.