Geburt der Götter

There are years when nothing is wrong, exactly, yet something is unmistakably missing. On paper, my life reads like a well-designed product. Stable, feature-rich, and reliably shipping. I’ve had a long and fortunate career as a product leader. I’ve built things I’m proud of, worked with people I respect, and earned credibility the slow way. During the pandemic I went back to school. Quietly, persistently, and finished a degree majoring in literature, culture and tradition at the University of Pennsylvania. I’ve traveled widely. I’ve fallen in love with languages, and adore the way they widen the shape of a day. Italian and French are now old friends. This year, Rome and Paris. Next year, Athens and Vienna. German, newer, tougher, strangely exhilarating.

I’m also a husband in a marriage which feels like a true partnership. A dad to a teenager who is steady and a good kid. A household which includes two cats and a beloved dog. The kind of domestic constellation that, if you described it to someone else, might sound like a small miracle of normalcy. And yet.

Somewhere in the middle of all that competence and gratitude, I started to notice a hollow note. Work, often wonderful, prestigious, meaningful in the abstract, began to feel like a place where my best self only partially arrives. I am proud to work where I do and I’m incredibly grateful for the opportunity to get to do what I do. The role is not cruel. It’s not chaotic. It’s not broken. I still love the work. But it is, increasingly, administrative. It’s a lot of managing, calibrating, aligning, maintaining. A lot of being responsible. And the increasing commute into New York, long, grinding, physically and emotionally subtractive, only amplifies a sense that the days are being spent, not lived.

Post-degree, I wasn’t exhausted in the classic sense. I was tired in a quieter way. The kind of tired which shows up as sadness without a clear narrative. The kind of tired which isn’t fixed by a few days off. I began to recognize that I didn’t feel creatively fed. I could still perform. Still deliver. Still lead. But I could feel the distance between the person I am becoming and the version of me my job routinely requires.

That’s the moment aufbruchmatt was born. Not as an idea, exactly. More like a response. A small act of survival disguised as a project. Because here’s the thing I’ve learned (sometimes painfully) about high-functioning adults. We can mistake competence for wholeness. We can confuse the ability to keep the machine running with the feeling of being alive. We can win the career game and still lose contact with the interior self that made us interesting in the first place.

When I finally said it out loud. I feel like there’s a hole in me. The answer which came back wasn’t a diagnosis or a pep talk. It was a reframe which landed with the unmistakable click of truth. You are not lost. You are underfed.

Underfed isn’t dramatic. It isn’t a crisis. It’s simply what happens when your life becomes optimized for responsibility, mastery, and output. While your inner life begins craving beauty, depth, and self-expansion. Not as hobbies. As vital signs. Proof that the self is still growing. This is where opera enters the story.

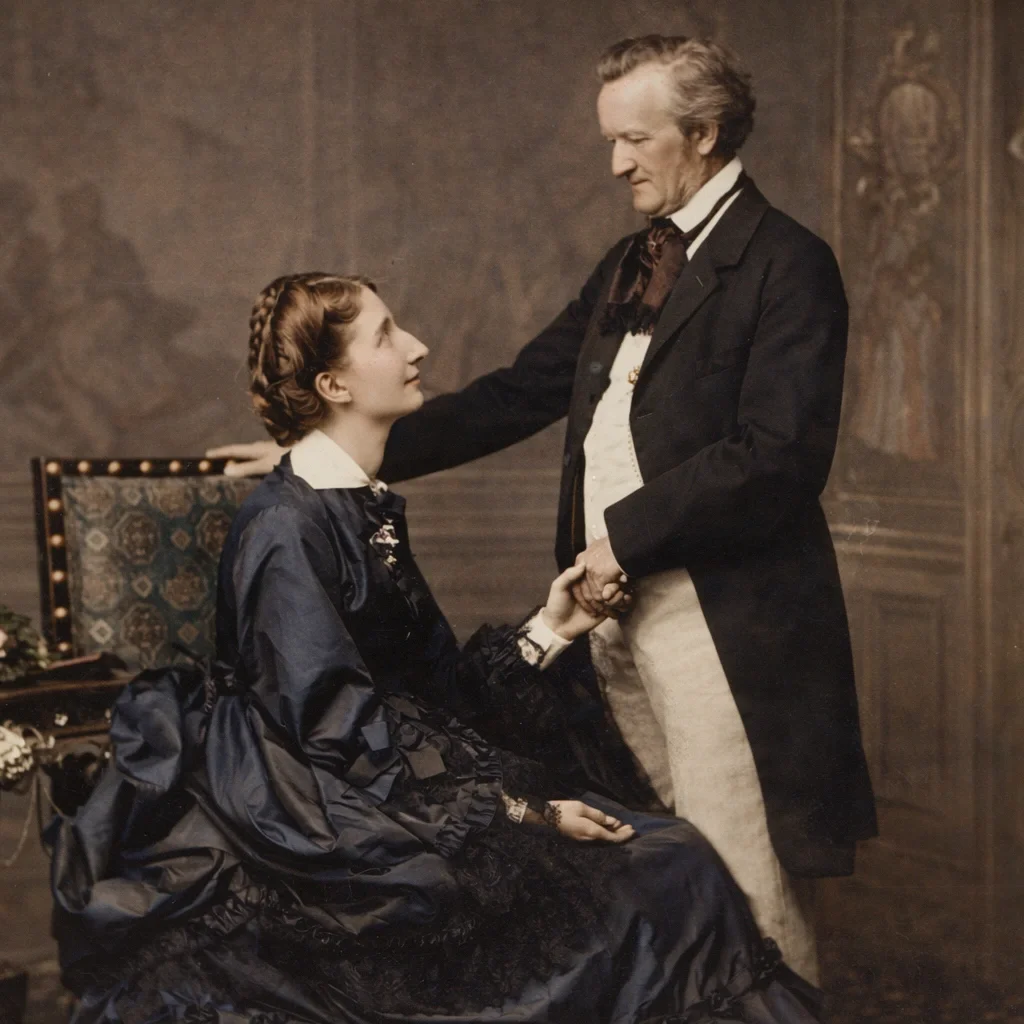

I fell into opera the way people fall into certain cities or certain books. Almost accidentally, then all at once. I went to a couple of performances this year. Watched the wonderful Met Opera productions online. Joined the Wagner Society of New York. And I noticed something subtle but unmistakable. My nervous system changed. My attention softened. My thinking became spacious. The world, briefly, regained dimension. Opera did not feel like entertainment. It felt like nourishment. Like a return to something older and larger than the treadmill of modern productivity. It carried myth. It carried time. It carried a kind of emotional honesty we rarely permit ourselves in ordinary life. And Wagner, especially Wagner, offered something else. Structure.

Not the corporate kind. The human kind. The kind which turns a year into a narrative arc, rather than a blur of meetings and commutes and emails. The kind which lets art become a companion instead of a special occasion. So I started with a simple, almost audacious proposition. What if I lived alongside Wagner for a year? Not as homework. Not as fandom. Not as an achievement badge. But as a slow, intentional creative pilgrimage. A way to augment my learning German. A way of giving my weeks a different spine.

One opera per month. A musical landscape to inhabit. A mythic weather system to walk through. A reason to read, to listen, to notice, to write. A reason to reclaim New York as something other than a workplace I commute in and out of. That last part mattered more than I expected. Because as soon as I began thinking about nourishment and restoration, my instinct was not to flee the city. I didn’t want escape. I wanted rediscovery. I wanted New York to re-enchant me again. To become a place that gives back. That’s how the Creative Circuit was born. An after-work ritual designed not for productivity, but for aliveness.

The idea was disarmingly simple. Once a week, after work, I would step out of the building and declare a small intention. This is my hour of beauty. I would walk a new path. Sometimes only slightly new. Enter a space which has atmosphere. A cathedral, a bookshop, a museum lobby, the Winter Garden at Brookfield Place, the quiet edge of the Hudson. I would sit for ten minutes. I would write one sentence. Not a journal entry. Not a post. One sentence which proves I was paying attention.

A ritual this small sounds almost laughable in the face of existential weariness. And yet small is often how change begins. Not with reinvention, but with a wedge. A crack in the sealed container of routine. Battery Park City became the first circuit because it holds something New York rarely offers, horizon. Water. Soft light. A European waterfront feeling. The Esplanade. The Irish Hunger Memorial. The hush of Rector Park. The Winter Garden’s vaulted glass. Robert F. Wagner Park staring out toward the harbor like a quiet, liturgy-sized exhale. All of it paired with Wagner’s Der Fliegende Holländer. In that neighborhood, the city doesn’t shout. It breathes.

From there, the project began to expand naturally. Like a map filling itself in. Upper East Side paired with Lohengrin. Tribeca with Rienzi. A subway-style poster language which makes the circuits feel like a transit system for the soul. Nodes, lines, interchanges, mood-based routes. A way of turning where should I go tonight? into what does my inner life need tonight?

And then the pieces clicked into a single architecture: Wagner as the year’s soundtrack. New York as the year’s studio. Walking as the method. One sentence as the artifact. If you zoom out, aufbruchmatt is not really about Wagner. And it’s not really about New York. It’s about the recognition that my sadness wasn’t a defect. It was a compass.

It was pointing to unmet needs. More beauty than process. More meaning than efficiency. More agency than administration. More depth than speed. More coherence between who I am at work and who I am everywhere else. This is the part that matters most to me, and the part I want to be honest about on this site. Sometimes these mid-career thoughts aren’t a crisis of success. They’re a crisis of self containment. The feeling that one’s life has become a stable box which no longer fits the expanding shape of our interior world.

The solution, at least for me, is not burning everything down. It’s redistributing identity. Letting work remain important without letting it remain central. Letting creativity lead again. Not as a monetized hustle, not as a brand, but as a source of oxygen. That’s what this site is for. A record of a year spent walking with myth. A diary of small pilgrimages through the city. A place to document circuits and listening plans and the strange, quiet ways a life can come back online.

Aufbruch is a German word which carries both departure and beginning. Breaking camp. Setting out. The moment you stop living in maintenance mode and start moving toward something. Without fully knowing what it is yet. That’s where I am. Not lost. Just finally, deliberately, learning how to feed myself again.

And if you’re reading this with a version of that same quiet hollowness, if your life looks good and still feels thin, then maybe you’re not broken either. Maybe you’re just underfed. And maybe this is what the first step looks like. One hour of beauty, one walk, one act, one sentence. A year begins that way.