Against the Contract: Brünnhilde, Ripley, and the Ethics of Refusal

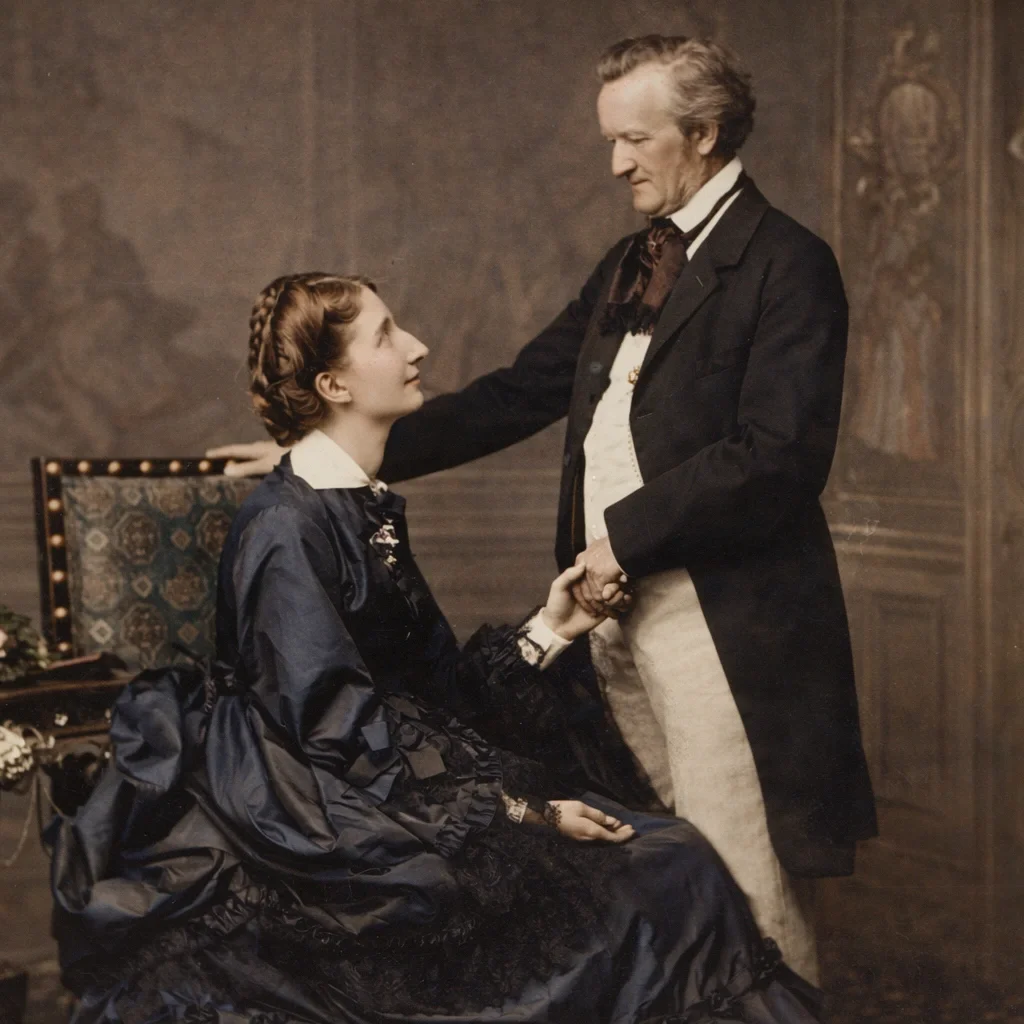

The most radical thing Brünnhilde does in Die Walküre is not her defiance of Wotan, nor her protection of Siegmund, nor even her willingness to accept punishment. It is something quieter and more devastating. She withdraws legitimacy. She recognizes that the law she was created to enforce no longer deserves obedience, and she acts accordingly. Not to seize power, not to replace the system, but to refuse its claim on her conscience. That act, more than any spear or flame, is what carries Wagner’s moral universe forward.

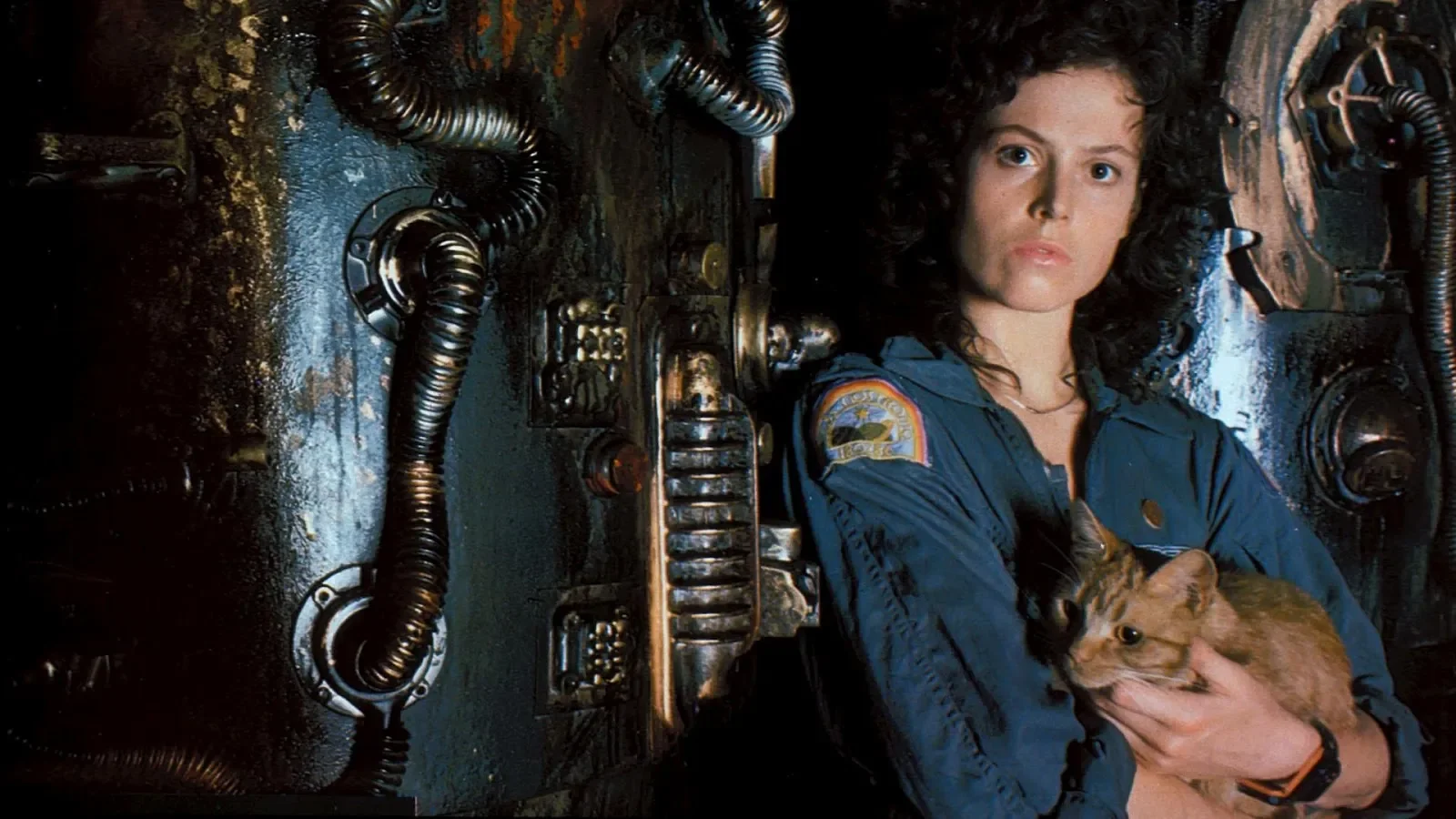

Ellen Ripley belongs to this lineage.

The Alien films are often discussed as horror, or as feminist revision of action cinema, or as industrial paranoia. All of that is true. But at their ethical core, especially in Alien and Aliens, they are Brünnhilde narratives displaced into late-capitalist space. They are stories about what it means to act morally inside systems that have replaced law with contract, authority with procedure, and meaning with profitability.

Wagner understood that the most dangerous systems are not overtly cruel. They are systems which continue to function after the values that once justified them have hollowed out. In Die Walküre, Wotan’s tragedy is not that he lacks compassion, but that he has built a world in which compassion is structurally illegitimate. The laws he creates are meant to stabilize power, but they also make ethical responsiveness impossible. When love appears, messy, human, unsanctioned, Wotan sees its necessity and yet cannot permit it without collapsing the order he has sworn to uphold. Weyland-Yutani is Wotan’s final form.

It is law without mythology, authority without presence. It does not argue, persuade, or even threaten. It simply cites policy. Its power is not personal. It is contractual. The Company does not want the alien because it hates human life. It wants the alien because the system has already decided that crew expendable is an acceptable clause. This is Wagner’s nightmare modernized. A world where no god must give the order, because the order has been embedded in procedure. Ripley’s significance lies in her refusal to accept that embedding as morally binding.

In Alien, Ripley is not initially heroic. She is procedural. She follows quarantine protocols. She argues for containment. Her authority emerges not from rebellion, but from competence within the system. This is crucial. Brünnhilde, too, begins as an enforcer. She does not question Wotan’s commands until she encounters a situation that exposes the law’s inability to account for lived human consequence. For Ripley, that exposure arrives when the Company’s priorities surface. Not through ideology, but through Ash.

Ash is the perfect Wagnerian intermediary. Like Hunding or the lesser gods, he is not evil in the melodramatic sense. He is faithful. He executes his orders with chilling purity. He admires the alien not because it is monstrous, but because it is efficient. In him, we see the future Wotan was trying to engineer. Obedience without anguish, execution without doubt. Ash’s loyalty is what makes him horrifying. He is what Brünnhilde refuses to become.

Ripley’s confrontation with Ash is therefore not a battle against a traitor, but against the system made flesh. When she learns the truth, that the crew was never the priority, her response is not ideological outrage. It is withdrawal. She no longer recognizes the Company’s authority as legitimate. From that moment forward, her actions are no longer governed by policy, but by care. She does not replace the system. She exits it. This is Brünnhilde’s move.

When Brünnhilde shields Siegmund, she is not overthrowing the gods. She is acknowledging that the gods have already failed. Her punishment, sleep, fire, exile, is not simply retribution. It is the system’s immune response to conscience. Wotan does not punish Brünnhilde because she is wrong. He punishes her because she is right in a way the system cannot absorb.

Ripley undergoes the same arc in Aliens. The film is often remembered for its militarization, its spectacle, its iconic one-liners. But structurally, it is a refinement of the ethical problem introduced in Alien. The Company now knows exactly what it is dealing with. The system has learned. It sends Marines, administrators, protocols. Everything is proceduralized. And yet the moral failure deepens.

Carter Burke is not a villain in the traditional sense. He is polite, affable, reasonable. He believes in process. His betrayal is not an act of malice, but of optimization. He sees Ripley not as a moral agent, but as a risk variable. This is Die Walküre in corporate dress. The moment when authority understands the cost of compassion and decides it is too high.

Ripley’s response is not rebellion for its own sake. She does not attempt to expose the Company publicly. She does not seize command of the mission. She does something more radical and more Wagnerian. She prioritizes the vulnerable over the system’s goals, even when doing so renders her actions illegible within institutional logic. Her relationship with Newt is central here, and not for sentimental reasons. Newt is Siegmund in miniature. A life the system has already written off as acceptable loss. Ripley’s protection of Newt is Brünnhilde’s protection of Siegmund stripped of myth and placed inside maternal ethics.

This is where Ripley departs decisively from the action-hero tradition. Her courage is not oriented toward victory, but toward preservation. She does not fight to win. She fights to prevent further moral erosion. The iconic confrontation with the Alien Queen is not a duel between equals. It is an act of boundary enforcement. Ripley is not asserting dominance. She is saying this far, and no further.

Wagner’s Brünnhilde undergoes a similar transformation across the Ring. She moves from enforcer to dissenter to bearer of future possibility. By the time of Götterdämmerung, she is no longer interested in salvaging the gods’ world. She understands that systems built on renunciation and extraction cannot be reformed. They must be relinquished. Her final act is not conquest, but release.

Ripley never burns the Company’s Valhalla. But she does something just as devastating. She survives. She persists as an ethical anomaly the system cannot assimilate. Even when later films attempt to absorb her into cloning, replication, commodification, her moral posture remains disruptive. She refuses to become procedural. She refuses to treat life as an acceptable variable.

This is why Ripley feels Wagnerian in a way few cinematic heroes do. She is not motivated by destiny, revenge, or transcendence. She is motivated by refusal to allow abstract systems to override embodied care. Wagner understood that this kind of refusal is the seed of a future that cannot yet be articulated. Brünnhilde does not build a new order. She makes space for one by exposing the old order’s bankruptcy.

What Ripley shows us is that in a post-mythic world, Brünnhilde’s task has not disappeared. It has become harder. There are no gods to confront, no divine fathers to disobey. There are only contracts, clauses, incentives, and risk assessments. Ethical action now requires something Wagner intuited but could not fully imagine. The courage to step outside systems that will never announce themselves as unjust.

In both Die Walküre and Alien, the tragedy is not that authority is cruel. It is that authority is indifferent. And the heroism is not that someone seizes power, but that someone refuses to lend their conscience to a machine that no longer knows what it is doing. Ripley, like Brünnhilde, does not save the world. She saves what the world would otherwise discard. And in doing so, she carries forward the only form of hope Wagner ultimately trusted: not the redemption of systems, but the survival of ethical clarity in spite of them.