The Valkyrie Who Walks Away: Brünnhilde, Furiosa, and the Ethics of Exit

There is a way of reading Brünnhilde which flatters us. Brünnhilde as icon. Brünnhilde as warrior. Brünnhilde as operatic spectacle. Helmet, spear, the Ride, the whole familiar mythology of force. But the Brünnhilde which actually matters, the one Wagner invents as his moral engine, is not primarily a figure of violence. She is a figure of refusal. Her power is ethical before it is martial. She does not change the world by defeating the system on its own terms. She changes the world by withdrawing herself from the system’s legitimacy, and by carrying the vulnerable beyond its reach.

This is why she maps so cleanly, so unsettlingly, onto Imperator Furiosa.

Mad Max: Fury Road is regularly praised as a masterpiece of action design, a ballet of momentum and dust. But its true radicalism lies in the fact that it is an action film built around an anti-imperial premise that is more Wagnerian than it first appears. That liberation is not achieved by capturing the throne. Liberation is achieved by leaving the throne behind. The film’s deepest argument is not about overthrowing a tyrant. It is about exiting an entire ontology of domination.

In Wagner’s Die Walküre, Brünnhilde stands at the moment when the old world first becomes ethically unbearable. She is born inside Wotan’s order and tasked with enforcing it. Her rebellion begins not as ideology but as perception. She sees the human cost of divine law and cannot unsee it. Siegmund’s love, Sieglinde’s fear, the brutal legitimacy of their illegitimacy. These experiences reveal that the system has outlived its moral warrant. What Brünnhilde ultimately refuses is not Wotan as father, but Wotan as structure. Law that demands sacrifice of life in order to preserve its own coherence.

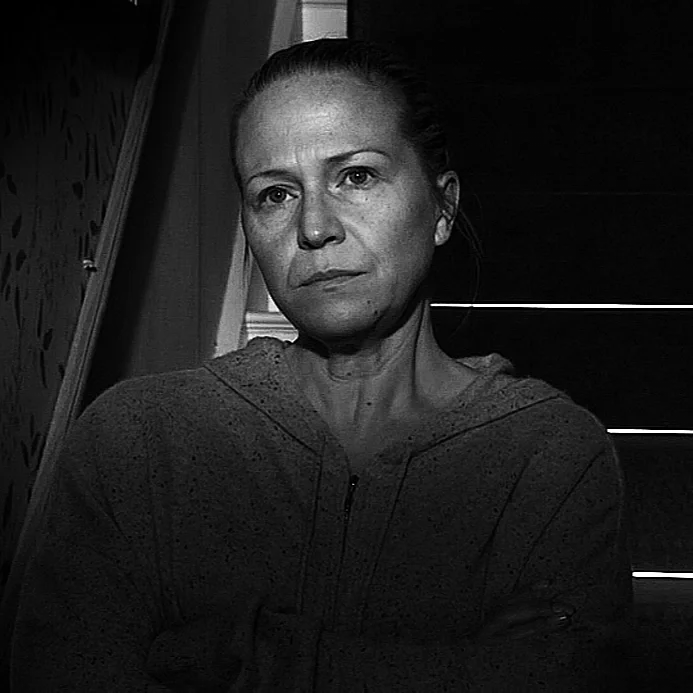

Furiosa is what Brünnhilde looks like when there is no longer any Wotan to mourn.

Immortan Joe is not a tragic authority. He is a grotesque infrastructure of scarcity. A body wrapped in ritual to disguise the fact that the world has already ended. The Citadel is not a kingdom in the operatic sense. It is an extraction engine. Its religion is not metaphysics. It is logistics. Water is withheld to manufacture dependence. Women are reduced to reproductive apparatus. Boys are turned into disposable fuel for war. If the Ring is Wagner’s portrait of a world collapsing under the contradictions of its contracts, Fury Road is the world after collapse. When contracts have been replaced by pure material control.

This is why Furiosa’s act is so radical. She does not seek reform. She does not petition. She does not attempt to make the Citadel more humane. She takes the people the system is built to consume and removes them from the system’s geography. The War Rig is not just a vehicle. It is a philosophical statement. It is the possibility of movement not as conquest, but as escape.

Brünnhilde’s protection of Siegmund in Walküre is the first such statement in Wagner. It is a refusal to allow the vulnerable to be processed by the machine. It is also, crucially, a refusal to treat love as a private sentiment irrelevant to politics. Brünnhilde’s compassion is not soft. It is insurgent. It threatens the gods’ order precisely because it asserts that the system’s laws are answerable to lived human consequence.

Furiosa’s compassion is insurgent in the same way, but in a world where consequence has become the only language left. When she turns the War Rig off route, she is not only betraying Immortan Joe. She is betraying an entire economy of meaning. The Citadel’s order is built on the assumption that there is nowhere else to go. Scarcity is not just material. It is existential. The tyrant’s deepest power is not violence. It is the foreclosure of imagination.

This is where the Brünnhilde mapping becomes especially sharp. Brünnhilde is the character who reintroduces imagination into a world that has hardened into law. She makes possible what Wotan cannot. A future not bound by his bargains. When Wotan surrounds her with fire, the most common reading is that he is punishing her while also protecting her. But the fire functions more deeply as a threshold. It declares that entry into the future will require a different kind of courage than obedience. Only someone willing to face danger without the guarantee of legitimacy can cross into what comes next.

Furiosa is surrounded by fire constantly. Fury Road is basically a continuous threshold.

But the film’s most Wagnerian move is its refusal to romanticize escape. Furiosa’s dream of the Green Place is not a utopia. It is memory. It is the desire to return to a coherent origin, a world where life wasn’t yet entirely instrumentalized. And Tarkovsky would recognize this immediately. Nostalgia as moral longing, not as sentiment. Furiosa believes, with a faith that is almost religious, that there is still a place outside the system’s logic.

When she learns the Green Place is gone, the film pivots into something far more profound. At this moment the story could have collapsed into despair, or into the typical post-apocalyptic cynicism that treats every ideal as naive. Instead, Furiosa does something Brünnhilde would recognize as the true test of ethical leadership. She revises her hope without abandoning it. She accepts that there is no return to origin. Therefore, the only liberation possible is to create a new locus of life inside the ruins.

This is, in compressed cinematic form, the transition Wagner spends the Ring building toward. The gods’ world cannot be restored. It must be relinquished. The question becomes, can something livable emerge without repeating the structures that destroyed the old world?

In Fury Road, the answer is yes, but not through conquest. It is yes through inversion. Furiosa returns to the Citadel not to occupy Immortan Joe’s throne in his image, but to break the scarcity machine that sustains him. The final ascent, Furiosa lifted upward on the platform as the people look on, is easily misread as coronation. It isn’t. It is the replacement of legitimacy. It is the crowd recognizing that authority derived from hoarding is illegitimate, and that authority derived from protection is real.

This is exactly what Brünnhilde represents. Authority that does not need law to justify itself because it is founded on care.

The crucial distinction is that both Brünnhilde and Furiosa embody what we might call the ethics of exit. They do not merely resist. They depart. They treat participation itself as the moral problem. This is why their actions feel so costly. A rebellion that seeks to seize the system is, in a strange way, still obedient to it. It accepts the system’s terms as the arena of legitimacy. Exit rejects the arena. Exit says, the world you have built is not just unjust, It is unworthy of my involvement.

Wagner was painfully aware of how rare such refusal is. Wotan cannot do it because he is too implicated. The gods cannot do it because they are the system. Brünnhilde can do it because she is inside but not identical to the structure. She is an agent of enforcement who becomes, through compassion, an agent of future possibility. And she pays the price. Isolation, sleep, the uncertainty of what comes next.

Furiosa pays the price too. Her body bears it. Her arm is gone. Her face is marked. Her authority is not clean or triumphant. It is forged in loss. This is why she is so compelling as a Brünnhilde analogue. She is not redeemed. She is not purified. She is simply the one who refuses to accept that the only choices are complicity or death.

And perhaps this is the deepest shared insight between Wagner and George Miller. That the future is made not by the strongest, but by the ones who can imagine a different structure of care and then endure the cost of acting as if that structure could be real.

Brünnhilde does not save the gods. Furiosa does not save the world. Neither is tasked with restoring an order that deserved to end. Their heroism is more severe. They salvage what the system would discard, and in doing so they preserve the conditions under which something new might begin.

If there is a Valkyrie in the modern imagination worth taking seriously, it is not the one who rides into battle to enforce old laws. It is the one who turns the War Rig away from the Citadel, crosses the desert with the unprotected, and then returns. Not to rule, but to end the economy of scarcity. That is Brünnhilde after myth, after gods, after hope has been stripped down to its only durable form: the courage to exit, and the courage to build.