What We Overhear Becomes Us: On Wagner, Jon Thompson, and The Quiet Architecture of Becoming

There are certain kinds of influence which don’t behave like influence at all. They don’t arrive with a manifesto, or a curriculum, or the clean certainty of mentorship. They arrive as atmosphere. A door half-open down a corridor. A muffled sound that you can’t immediately place. A feeling you register without language, filed away by the nervous system rather than the mind. Later, much later, it returns as if it were always yours.

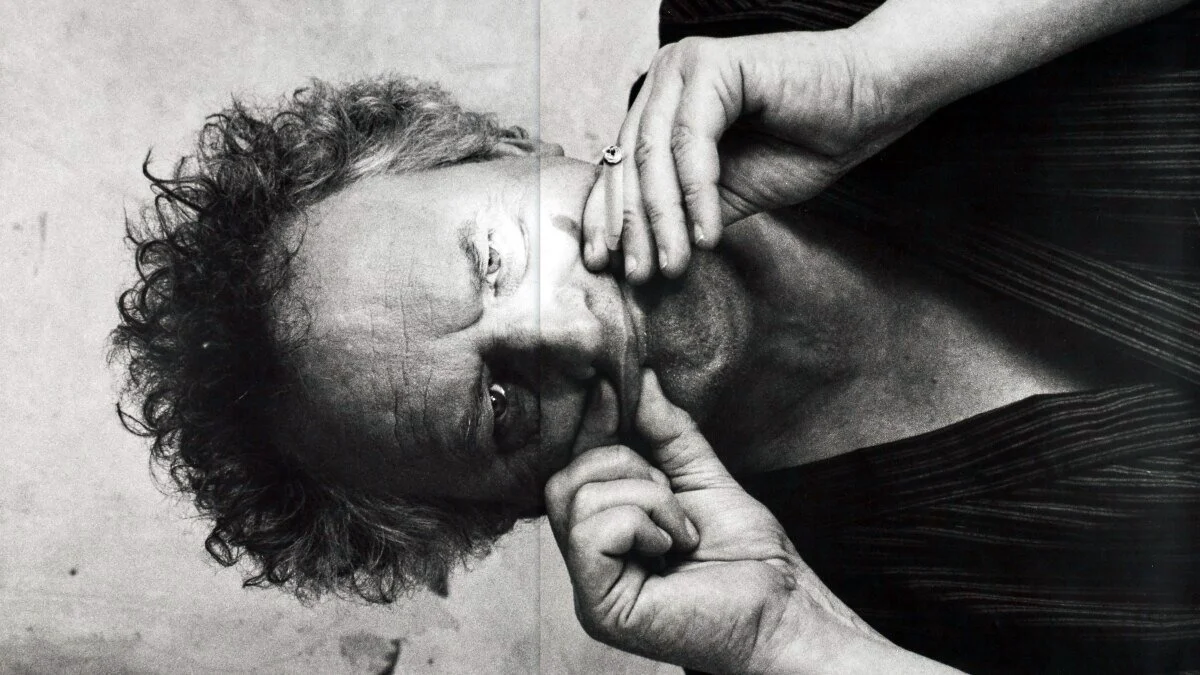

I keep coming back to Jon Thompson’s office at the Jan van Eyck Akademie, and to Wagner playing within, because it refuses to resolve into a simple story. It wasn’t a lesson, not explicitly. It wasn’t even, at the time, of interest. It was just part of the world. A grown man’s private ritual, a soundtrack to thinking, an almost comic intensity leaking into institutional air. But now, thirty years on, with Jon gone for years, with the Jan van Eyck years receding into that strange, varnished memory light, I realize what I miss isn’t merely him, or even that sound. What I miss is the concept of the unintended transmission. The way someone can plant a long-fuse charge inside you without knowing it, and without you consenting, and without the culture around either of you noticing that anything happened.

In the AufbruchMatt project, I’ve been circling a similar phenomenon. How a work can become a map for a life long after it stops being a work. How Wagner, problematic, grandiose, tender, monstrous, can become not simply a composer but a way of metabolizing time. A way to turn a city into a libretto. A way to give structure to longing. A way to make learning German feel like something more than vocabulary and conjugations. A form of apprenticeship to a mind, a mood, a national argument, a set of mythic gears.

But what I hadn’t fully seen, until I held Jon’s office up against this whole arc, is that the real through line may not be Wagner at all. The through line might be the mechanics of return.

Because return is not nostalgia. Not exactly. Nostalgia is sentimental. It makes the past sweeter than it was and the present poorer than it needs to be. Return is different. Return is forensic. Return is the mind re-opening an old folder because some new piece of evidence has appeared, and the case file can finally be understood. You don’t return because you want to feel young again. You return because the meaning wasn’t available to you then. You return because you’ve become the person who can read your own earlier life.

And that, in its own odd way, is a very Wagnerian idea.

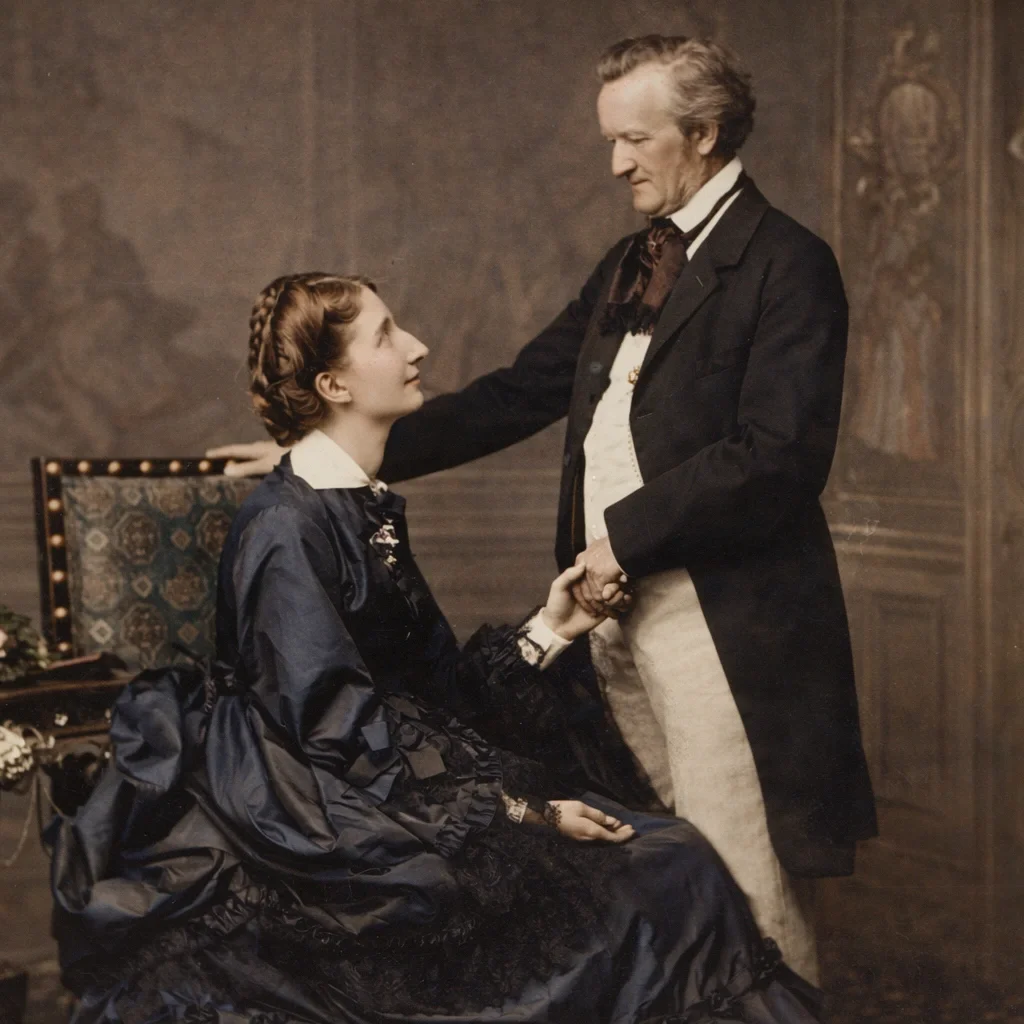

Wagner’s characters are always arriving too late to understand what they already belong to. Siegmund discovers he is standing inside a story written before his birth. Brünnhilde awakens to a morality she didn’t know she had. Parsifal becomes wise through compassion only by wandering in error. Even the Ring itself behaves like an intergenerational infection. A curse which travels along bloodlines and institutions, changing shape, waiting for the right host. The tragedy is not simply what happens. The tragedy is how long it takes anyone to see what is happening.

When Jon played Wagner in his office, he was doing something artists and educators do constantly. Building an internal weather system which lets them think. Everyone has their weather. Some people need silence. Some need jazz, or punk, or Bach, or the hum of an espresso machine, or the low-level cortisol of a newsroom. Jon needed Wagner. Long arcs, moral storms, myth as an organizing principle. He was curating his own cognitive container.

Here’s the first thing which surprises me when I look at it this way. Jon may have been teaching you something important not through critique, or guidance, or taste-making, but through self-regulation. Through the unapologetic act of choosing an environment that made his mind possible. The lesson wasn’t that Wagner is great. The lesson was, if you want to make serious work, you have to protect the conditions in which seriousness can occur. You have to be willing to be a little strange about it. A little intense. A little unrelatable. You have to build a room in which thinking can happen and then, crucially, you have to inhabit it like you mean it.

That’s an educator’s gift which often goes unacknowledged. Not instruction, but permission.

Because permission is a form of inheritance. And inheritance is not always financial. Sometimes it is aesthetic. Sometimes it is behavioral. Sometimes it is the simple revelation you are allowed to care this much.

Thirty years later, I’m running a project which is, in its quiet way, an act of permission-making for myself. The AufbruchMatt circuits, the pairing of operas with ferry rides and city corners and subway stops, are not merely clever mappings. They are a declaration that an inner life deserves infrastructure. That passions deserve a calendar. That the practice of attention deserves a system. That wonder is not a guilty pleasure but a serious mode of living.

Which leads to the second thing I hadn’t noticed until Jon entered the frame. This isn’t just about Wagner returning to me. It’s about Jon returning to me through Wagner.

When someone dies, there’s a temptation to think the relationship ends and grief begins, as if the two are sequential. But one of the strangest truths is that relationships can become more complex after death because they stop accumulating new data and start being reinterpreted. The person becomes, in a sense, a text. Not in a reductive way, no one is just a text, but in the way that you now only meet them through memory, and memory is an act of editing. Over decades, you don’t remember the facts. You remember the meaning you made from the facts. That meaning changes as you change. So the person continues to evolve, not in the world, but inside you.

This is where the AufbruchMatt project intersects with my deeper preoccupations. Attention, memory, agency, the ethics of technology, the strange economy of what we consume and what consumes us. Because the Jon/Wagner imprint suggests that our lives are shaped less by singular epiphanies than by repeated micro-exposures. The tiny cues that tell our brains what a supposed real life looks like. An office with Wagner playing is one of those cues. It says, there is such a thing as a life organized around thought. There is such a thing as a person who lives in conversation with art rather than merely enjoying it. There is such a thing as intensity that is not performative.

The third insight hiding in this story is maybe the most personal. My passion for Wagner now may be, partly, a form of belated dialogue with Jon. An attempt to answer a question he asked without asking it.

In creative education, the visible currency is feedback. What the teacher says about the work. But the invisible currency is something else. A student’s dawning awareness that the teacher is also a person wrestling with the world. A student sees the teacher’s rituals and realizes, adulthood can be built. Aesthetic life can be sustained. The teacher becomes evidence that a certain kind of existence is viable.

When I think about Jon’s office now, I’m not just remembering Wagner. I’m remembering a model of adulthood. Not the conventional adulthood of career ladders and retirement accounts, but the adulthood of cultivated obsession. Of choosing a thread and following it until it becomes a rope bridge between decades.

The rope bridge I’m walking now.

Because my current life, executive responsibility, product leadership, a career built on systems and impact, could easily crowd out the kind of slow, ardent, unproductive love Wagner demands. Yet I have built an apparatus to keep it alive. A year-long calendar, city circuits, language study, essays, generative podcasts. I refuse the false binary between professional success and aesthetic devotion. I have turned devotion into a product in the best sense. Something designed, scheduled, shipped, iterated.

This is where I think the story becomes unexpectedly moving. Not in a sentimental way, but in a structural way. Jon’s Wagner wasn’t just music in an office. It was an early proof that private passion can survive inside public institutions. That someone can carve out a pocket of myth in a building full of administrative reality. That the sacred can leak into the everyday.

And now I’m scaling that leakage into an entire project. One more turn of the screw. Wagner’s music dramas are obsessed with the costs of inheritance. The way what we receive shapes what we are allowed to become. Alberich’s curse is a kind of ancestral debt. Wotan’s laws become a trap of his own making. The world collapses not because the characters lack power, but because they inherit systems that make their power self-defeating.

In that light, Jon’s inadvertent influence becomes a counter-inheritance. Not a curse, but a counter-curse. A gift that doesn’t bind me to his life, but quietly expands what I believe life can contain. The most radical part of that gift is that it arrives without obligation. Jon didn’t ask me to become a Wagnerian. He didn’t assign me a pilgrimage. He didn’t leave me a syllabus. He simply lived in a certain frequency, and I heard it. Decades later, when my own life needed a frequency like that, a way to metabolize ambition and time and meaning, I found it already inside me, waiting, like a motif that had been introduced in Act I and finally earns its resolution in Act III.

Some influences are not directives but motifs. They don’t tell you what to do. They return when the narrative requires them.

And perhaps this is what I’m really building with AufbruchMatt. A way to notice motifs before I miss them. A method for walking through my own life with the attentiveness of a composer. To ask, each month, not only what opera am I listening to? but what long-forgotten material is returning now, and what is it trying to complete?

Jon Thompson, in an office in the Netherlands, playing Wagner. An atmosphere, a weather system, a private ritual, might be one of those motifs. Not because it explains everything, but because it proves something which feels essential. That the deepest parts of us are often formed in overheard moments, and that time does not erase those moments so much as wait until we are finally ready to hear what they were saying.