Against Total Immersion: Wagner, Blade Runner, and an Architecture of Meaning

There is a line which people always quote from Blade Runner, but very few linger over its most radical implication. When Roy Batty says that he has seen things you people wouldn’t believe, the speech is usually taken as a lament for mortality, or a poetic expression of memory’s fragility. But what Batty is really naming is a boundary condition. A threshold at which experience becomes untranslatable. He is standing at a gate between worlds. Between what can be carried back into shared culture and what must vanish with the witness.

That same gate stands at the center of Tannhäuser, though Wagner names it very differently. To understand that gate, and to understand why it matters in a way that goes beyond the biography of my own project here, real-world operatic discovery, or even language learning, we need to stop thinking of Wagner as merely a composer of excess and start seeing him as one of the earliest theorists of perceptual thresholds.

Wagner’s world is obsessed with crossings. Gods descend. Humans ascend. Lovers cross moral law, social law, and metaphysical law. But Tannhäuser is the opera where Wagner makes the crossing itself the subject. The Venusberg is not simply a place of erotic excess. It is a perceptual regime. Inside it, desire is total, continuous, and self-reinforcing. Time collapses into sensation. Memory loses its narrative structure. Meaning no longer accumulates; it saturates. Tannhäuser’s crisis is not that Venus is sinful, but that the Venusberg abolishes distance. Without distance, nothing can be remembered, judged, or redeemed.

This is where the so-called Tannhäuser Gate, borrowed linguistically by Blade Runner but conceptually Wagnerian long before it, reveals its deeper significance. The gate is not a location in space. It is a cognitive and moral boundary between experience that can be integrated into a life and experience that overwhelms the structures by which life becomes intelligible.

Wagner understood this intuitively. His operas are often misread as indulgent, but structurally they are exercises in restraint. Think of how often Wagner delays resolution, defers gratification, stretches harmonic tension past comfort. This is not decadence. It is pedagogy. Wagner forces the listener to remain conscious of longing rather than dissolve into it. The Venusberg music is intoxicating precisely because it cannot last. It must expel Tannhäuser, or the opera would collapse into formlessness.

Now return to Roy Batty in the rain. His monologue is not a confession. It is a refusal. He names experiences. Attack ships off Orion, c-beams glittering near the Tannhäuser Gate. Not to share them, but to mark their inaccessibility. The speech is an ethical act. He does not try to translate the sublime into spectacle or moral lesson. He allows it to perish intact. That restraint is what makes the moment human.

Here is the connective argument that tends to be missed. Wagner and Blade Runner are not united by romanticism or melancholy, but by a shared suspicion of total visibility. Both are deeply skeptical of worlds in which everything is seen, everything is felt, everything is consumed.

This project might be described, narrowly, as a Wagnerian walking diary, or a year-long aesthetic experiment. But its deeper function is regulatory. It is a self-designed system for approaching intensity without surrendering agency. By pairing operas with geography, language, walking, and time, I am constructing gates with agency and purpose. I am deciding where immersion begins and ends. I am refusing the Venusberg’s promise of frictionless transcendence in favor of something slower, structured, and narratable.

Wagner believed art could reframe perception, but he also believed that unbounded sensation was destructive. His essays are full of warnings about modernity’s tendency to overstimulate without educating, to flood the senses without forming judgment. Tannhäuser is his cautionary tale about a culture which mistakes saturation for fulfillment.

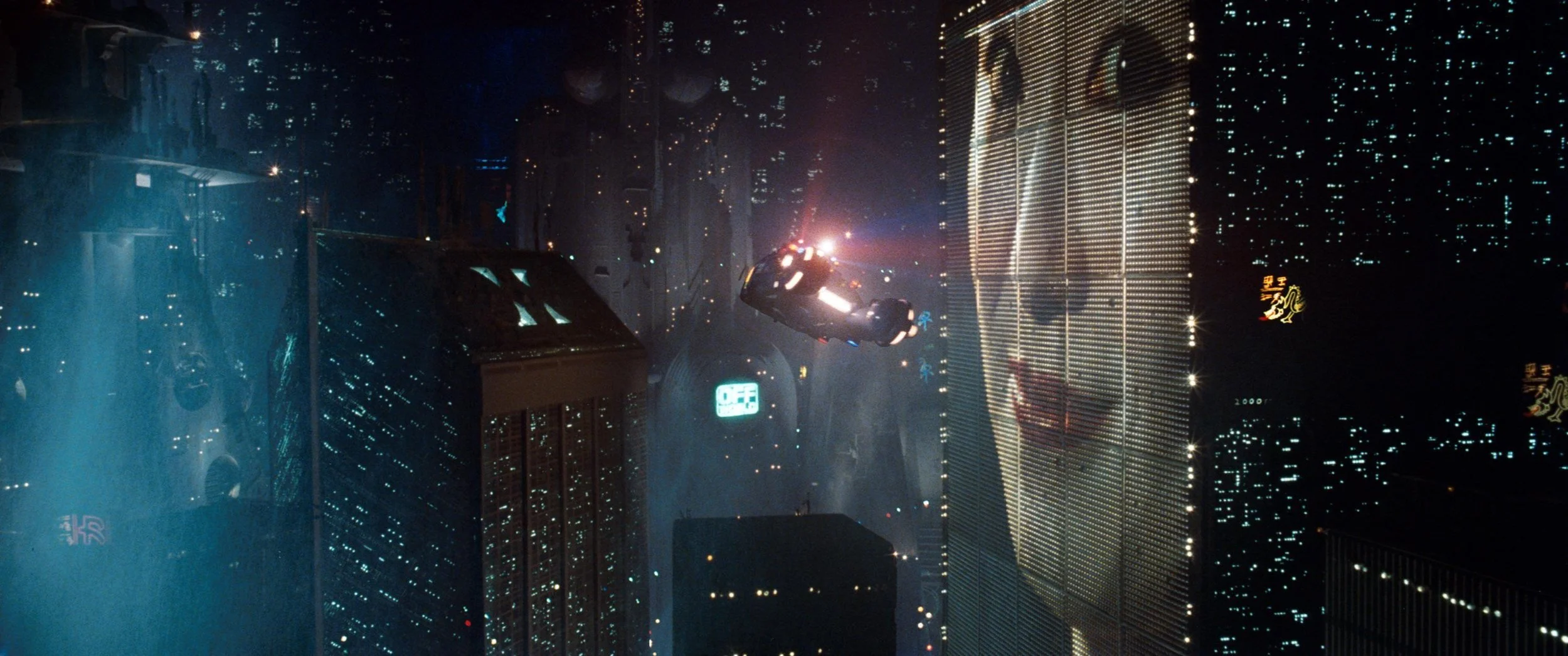

Blade Runner arrives at the same insight through science fiction. Its world is drenched in stimuli. Advertising, neon, rain, sound, but meaning is scarce. The replicants are not tragic because they are artificial. They are tragic because their experiences exceed the social structures capable of recognizing them. They live on the far side of the gate, where memory exists but cannot be archived.

The Tannhäuser Gate is not about death. It is about curation. What separates a life that coheres from one that dissolves is not the quantity of experience, but the presence of thresholds. Gates determine what enters narrative memory and what remains private, ineffable, or transient. Without gates, experience becomes noise. With too many gates, life becomes sterile. The art is in their placement.

AufbruchMatt, read this way, is not a retreat from ambition or achievement. It is an infrastructural response to abundance. I am designing a system which allows intensity to be metabolized rather than merely consumed. Walking routes, monthly operas, language listening, geographic specificity. These are not aesthetic flourishes. They are load-bearing constraints. Wagner would have recognized this immediately. He was obsessed with scaffolding experience so that it could be borne by the listener without annihilating them. Bayreuth itself is a gate. Darkened auditorium, hidden orchestra, ritualized entry. Blade Runner stages its gate as cosmic and unknowable, because its world has lost the institutions capable of holding it.

In that sense, Roy Batty’s tears are not about loss alone. They are about the tragedy of experiences that never found a form strong enough to survive them. Tannhäuser’s suffering is the inverse. He survives because he leaves the Venusberg, but he carries the cost of that departure forever. My project lives precisely inside such tension. It is an answer to the modern problem of infinite access and insufficient meaning. It demands, not everything should be seen at once. Not everything should be shared. Some things must be approached obliquely, slowly, on foot, in a foreign language, over time. The real gate, then, is not out there near Orion. It is the one you build into your own life. The threshold between consumption and comprehension. Wagner built operas to teach people how to cross it. Blade Runner mourns a world that no longer knows how. AufbruchMatt is quietly doing the work of such reconstruction.