Bloodline Against Law: The Empire Strikes Back, Die Walküre, and the Tragedy of Inherited Order

What makes The Empire Strikes Back endure is not its plot mechanics, nor even its famous revelation, but its refusal of narrative consolation. It is the rare popular film which ends not with victory deferred, but with the moral structure of the world itself destabilized. When mapped onto Wagner’s Die Walküre, the film’s deeper architecture comes into view. Both works are not stories of rebellion triumphant, but tragedies of inheritance. Of what happens when love, blood, and compassion collide with systems that were designed precisely to make such collisions impossible.

The Empire Strikes Back is often remembered as a dark Star Wars film, but darkness is the wrong category. The film is rigorous rather than bleak. It strips away the mythic clarity established in A New Hope and exposes the cost of moral certainty in a universe governed by institutions which predate the individual. This is exactly Wagner’s project in Die Walküre, the emotional and ethical fulcrum of the Ring. In both works, the central tragedy is not that good and evil are difficult to distinguish, but that the right action may be structurally illegitimate.

At the heart of Die Walküre is Wotan’s dilemma, one of the most devastating constructions in nineteenth-century art. Wotan, ruler of the gods, has bound the world together through law, contract, and oath. These structures are meant to secure order without constant divine intervention. But when Siegmund and Sieglinde fall in love, siblings, lovers, fugitives from a brutal social order, they embody something Wotan did not plan for. An ethic prior to law. Their love is not socially acceptable, not legally defensible, but morally coherent. Wotan sees this instantly, and that recognition destroys him. To save the system, he must destroy what he knows to be right.

This is the same tragedy which overtakes Luke Skywalker.

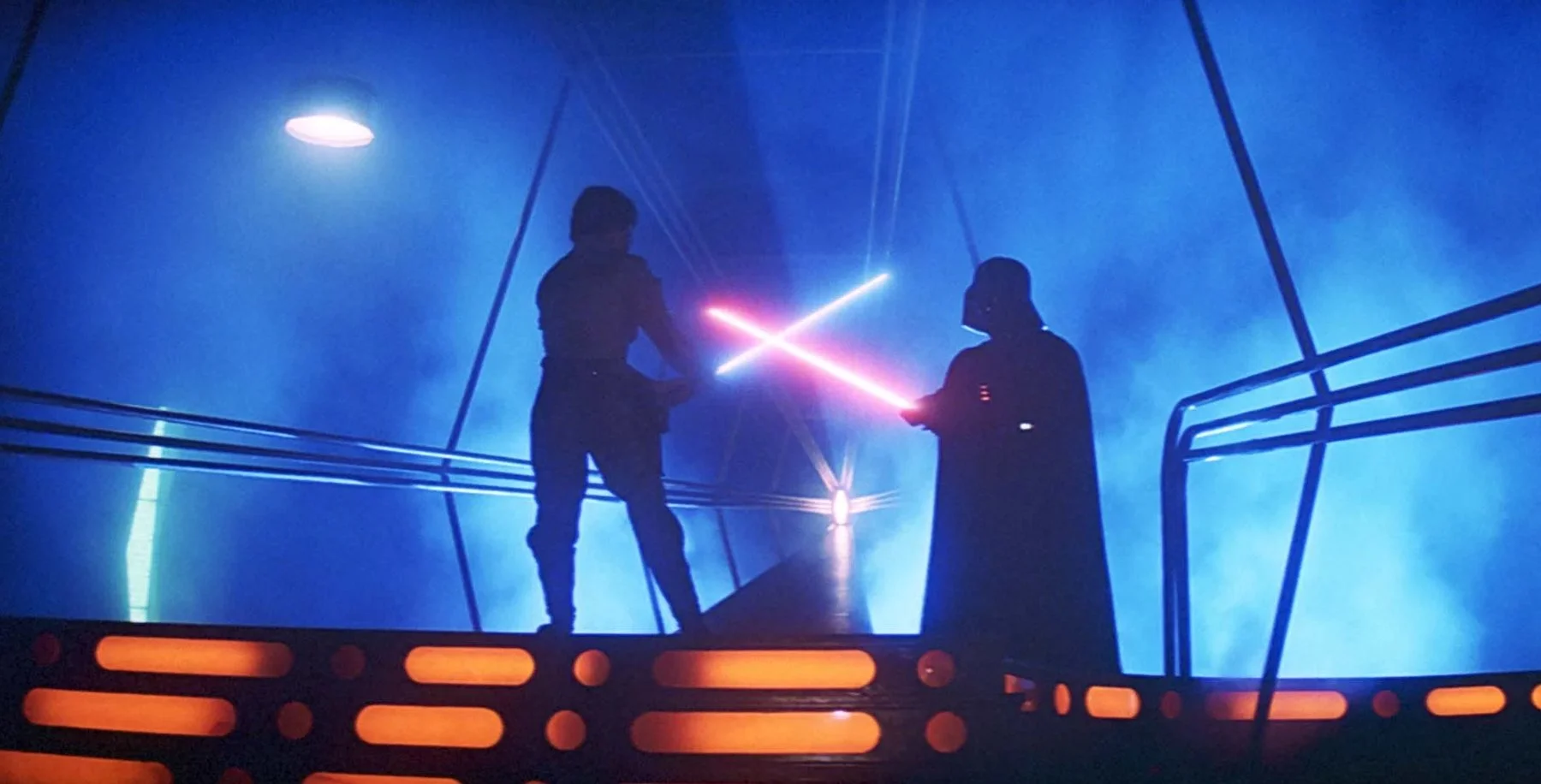

Luke’s journey in The Empire Strikes Back is frequently framed as a story of impatience or incomplete training. But that reading externalizes what is actually an ethical conflict. Luke does not fail because he lacks discipline. He fails because he refuses to abandon relational responsibility in the name of abstract order. His vision of Han and Leia suffering is not a trick alone. It is a test of allegiance. Will he remain faithful to a system, the Jedi code, which demands emotional detachment, or will he act on compassion, even if that compassion violates institutional wisdom?

Yoda and Obi-Wan function, in this sense, as Jedi Wotans. They are not villains. They are custodians of a fragile order which has already nearly collapsed. Their caution is not cowardice. It is historical trauma. They have seen what happens when rules bend. And yet, like Wotan, they are trapped by the very system they uphold. To preserve the future, they must suppress truth in the present. Hence the lie of omission. Hence the burden placed on Luke. Not merely to defeat Vader, but to do so without fully understanding who Vader is.

The revelation I am your father lands with the force it does not because it is shocking, but because it reframes the entire moral universe. Suddenly, the enemy is no longer external. Conflict is internalized into lineage. Luke is not simply fighting tyranny. He is confronting the possibility that evil is not an aberration but an inheritance. This is precisely Siegmund’s predicament. He is born into violence, raised by wolves, carrying a sword he does not fully understand. His defiance of Hunding’s law is not ideological. It is instinctive. He acts out of love because love is the only thing in his world that has not yet been codified into cruelty.

In Die Walküre, Brünnhilde becomes the moral hinge. She is tasked with enforcing Wotan’s will, yet she is moved by the human cost of that will. Her decision to protect Siegmund is not rebellion for its own sake. It is ethical disobedience. She recognizes that law has outpaced justice. When Wotan reverses himself and demands Siegmund’s death, the tragedy is complete. Authority knows it is wrong and acts anyway.

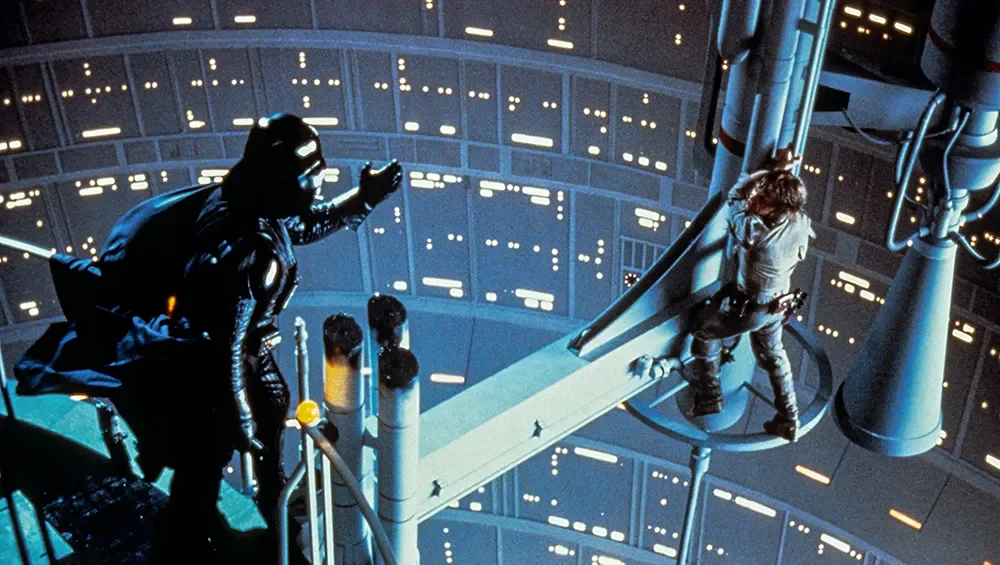

This maps directly onto Darth Vader’s role in The Empire Strikes Back. Vader is often misread as pure enforcer, but the film subtly undermines this. His pursuit of Luke is not merely instrumental. He wants Luke alive. He wants recognition, continuity, connection. Like Wotan, he is both architect and prisoner of the system he serves. The Empire is not sustained by Vader’s cruelty alone. It is sustained by his unresolved attachment. His offer to Luke, to rule together, is grotesque, but it is also the first moment in which the system admits its dependence on blood rather than ideology.

What neither work allows is a clean synthesis. The Empire Strikes Back ends in suspension. Luke maimed, Han frozen, Leia grieving, the Rebellion diminished. Die Walküre ends with Brünnhilde punished, exiled into sleep, surrounded by fire. These are not endings which reassure. They are endings that insist on duration. Ethical conflicts of this magnitude cannot be resolved in a single act. They must be carried forward, inherited, re-encountered.

This is the crucial insight both works share. Systems do not collapse when challenged by force alone. They collapse when confronted with love they cannot metabolize. Wotan’s law cannot account for Siegmund and Sieglinde without unraveling itself. The Jedi Order cannot account for Luke’s attachment without conceding that its own emotional austerity helped produce Darth Vader in the first place.

Seen this way, The Empire Strikes Back is not the dark middle chapter of a heroic trilogy. It is the Walküre of Star Wars. The point at which myth admits its own insufficiency. The rebellion is no longer about overthrowing an empire. It is about redefining what moral legitimacy looks like in a world where authority has outlived wisdom.

This is why Luke’s refusal at the end of the film matters so profoundly. He does not join Vader, but he also does not defeat him. He chooses non-assimilation over victory. He chooses fall over corruption. This is a Brünnhilde moment. An acceptance of punishment rather than participation in a system which demands ethical self-annihilation.

Wagner understood that the most dangerous systems are those which compel good people to do harm in the name of stability. George Lucas, and more importantly, Irvin Kershner’s direction, understood the same thing intuitively. The Empire Strikes Back does not ask us to cheer for rebellion. It asks us to sit with an unbearable truth. That the line between protector and oppressor is often drawn not by intent, but by structure.

In both Die Walküre and The Empire Strikes Back, the future is not saved by obedience. It is preserved, precariously, by acts of refusal which fracture authority from within. Love does not win. Compassion does not triumph. But something fragile remains intact. The possibility that the next generation might build a world in which law once again answers to life, rather than demanding its sacrifice.

That possibility is not hopeful in a sentimental sense. It is Wagnerian hope, and it is Star Wars hope at its most mature. Hope earned not through victory, but through the willingness to bear the cost of choosing rightly when the system insists you are wrong.